Emergency Reading

or, Never Without a Book

Up from Preliteracy

First there were the Darkest Ages of Preliteracy, when no one had anything to read because writing hadn't yet been invented. These were sad, hard times for our ancestors: after the typical sumptuous evening meal around the cave hearth, there was little to do except spray-paint animal caricatures on the cave walls, watch television by firelight, and play video games with wooden joysticks.

First there were the Darkest Ages of Preliteracy, when no one had anything to read because writing hadn't yet been invented. These were sad, hard times for our ancestors: after the typical sumptuous evening meal around the cave hearth, there was little to do except spray-paint animal caricatures on the cave walls, watch television by firelight, and play video games with wooden joysticks.

Then came agriculture, literacy, and history. Civilization! Writing to read. The long Preliterate night had ended, but this Sun of Words barely had peeped over the written horizon. Media were sharply limited to clay tablets, papyrus, vellum, stone monuments, and borderless Etch-a-Sketch on the sand dunes. Few people could read or write: Pharaoh's accountants and priests, long-distance traders, Pyramid engineers. Most writing was bookkeeping. For emergency reading, the literate few could wander over to a stele in the desert and read of some Pharaoh's achievements.

Yes, given writing, people began to want to read. Yet having anything at all to read remained uncommon for centuries. Manuscript copies are slow to produce, even without hand-painted illustrations and illuminated lettering. There still were no newspapers with wars and rumors of wars, no sports pages, no thrilling details of murders or school-board riots. The common man could only dream of such luxuries until Johannes Gutenberg's moveable, alphabetic type made the light burst brightly upon Europe. In a few short centuries of the printing press, everyone wanted sports pages and so forth.

With the spreading-wide of literacy, and general availability of at least crude printed matter, came a new need and with that, a new anxiety. From reading being a rare chore (for accountants, etc.) or rare luxury, it became an increasingly ordinary and expected necessity of life. Reading became important to vast numbers of people, for business, pleasure, diversion. Books moved down-market, brought ideas and places and wonders to the masses.

In 1894, Rudyard Kipling likened the big old-style, three-volume novel to a grand three-deck sailing ship, carrying us by a fair breeze and a broad keel to destinations beyond the horizon:

History and Poetry in the U.S. ArmyFull thirty foot she towered from waterline to rail.

It took a watch to steer her, and a week to shorten sail;

But, spite all modern notions, I've found her first and best —

The only certain packet for the Islands of the Blest. ...That route is barred to steamers: you'll never lift again

Our purple-painted headlands or the lordly keeps of Spain.

They're just beyond your skyline, howe'er so far you cruise

In a ram-you-damn-you liner with a brace of bucking screws. ...Rudyard Kipling

"The Three-Decker" (1894)

Rudyard Kipling's Verse,

Definitive Edition

I began my own literacy with a colorful cloth word-and-picture book, and alphabet blocks. I learned to read from looking over my Mother's shoulder as she read Donald Duck comic magazines to me, so without any perceived effort I could read before entering kindergarten. At breakfast I would read cereal boxes, milk-can labels, whatever was handy. The reading habit, strongly begun, continued.

I began my own literacy with a colorful cloth word-and-picture book, and alphabet blocks. I learned to read from looking over my Mother's shoulder as she read Donald Duck comic magazines to me, so without any perceived effort I could read before entering kindergarten. At breakfast I would read cereal boxes, milk-can labels, whatever was handy. The reading habit, strongly begun, continued.

In our literate, book-wealthy civilization we usually may count on reading material abounding: books, magazines, newspapers; even advertisements are sometimes amusing. But on going into the U.S. Army, I foresaw that access to my kind of read-stuff would be difficult at least at the beginning. So to Basic Training in Fort Ord, California, I brought an extra shaving-kit or small travel-kit, with several paperbacks inside. I chose thick ones that would give me a lot of hours per volume: The Viking Portable Thoreau (my Dad had gotten me interested in Walden some years earlier); The Viking Portable Milton (shorter poems as well as Paradise Lost); and Paul Murray Kendall's biography of Richard the Third (this solidified a boyhood interest in the Wars of the Roses).

In the evenings in Basic Training, sometimes we had only five or ten minutes of free time before lights out. Yet just a few pages of reading may put one's mind back into the real world, and truly aid the mental balance. Personal possessions were almost entirely forbidden — no civilian clothes, for instance — but a neat little stack of books inside that extra shaving-kit were passed with approval.

Later in Radio Telegraph School in Fort Ord, a friend with a portable radio happened on Beethoven's Ninth Symphony one summer evening, and he and I went out on the barracks porch and listened with pleasure. This convinced me I needed a portable radio, and I shortly bought one. But one cannot trumpet forth classical music in all situations, and sergeants sometimes express annoyance if a soldier is listening to music instead of to them. In any case, intellectual food is required too: books.

While later assigned by the U.S. Army to Kaiserslautern, Germany, I wrote home and requested my Mother to send me a copy of a favorite longish poem of mine, one of many that she'd read to me when I was little: "The Barrel-Organ" by Alfred Noyes. Here's a sample:

There's a barrel-organ carolling across a golden street

In the City as the sun sinks low;

Though the music's only Verdi there's a world to make it sweet

Just as yonder yellow sunset where the earth and heaven meet

Mellows all the sooty City! Hark, a hundred thousand feet

Are marching on to glory through the poppies and the wheat

In the land where the dead dreams go.So it's Jeremiah, Jeremiah,Come down to Kew in lilac-time, in lilac-time, in lilac-time;

What have you to say

When you meet the garland girls

Tripping on their way? ...

Come down to Kew in lilac-time (it isn't far from London!)

And you shall wander hand in hand with love in summer's wonderland;

Come down to Kew in lilac-time (it isn't far from London!)

She typed out a copy in several pages and mailed it to me. Very portable. I kept that poem buttoned into my shirt pocket to pull out and read while waiting in line or waiting for orders, both common activities in any era's army from Pharaoh's time onwards. Eventually I memorized substantial portions.

If I'm going to a restaurant or an airport and may be a while by myself, I'll take a book (history or current affairs, perhaps a translation of Goethe or Heine or Pushkin or Rilke) or a magazine (once possibly an old Astounding Science Fiction but those issues are getting delicate with time, so more likely a recent The Economist). Having useful or entertaining printed matter at hand is not nearly as vital as oxygen, not even as important as food or drink, but it's the mind's inspiration, the brain's subtle nourishment.

If I'm going to a restaurant or an airport and may be a while by myself, I'll take a book (history or current affairs, perhaps a translation of Goethe or Heine or Pushkin or Rilke) or a magazine (once possibly an old Astounding Science Fiction but those issues are getting delicate with time, so more likely a recent The Economist). Having useful or entertaining printed matter at hand is not nearly as vital as oxygen, not even as important as food or drink, but it's the mind's inspiration, the brain's subtle nourishment.

On auto trips I always have several books to read not counting guidebooks, and even on errands when I may wait for someone, I'll bring the current book; if it's a book for review, I'll be taking notes. Of course, for many drivers there's also the glove compartment stuffed with Auto Club maps, and several Thomas Brothers map books to browse, for those who like maps as I do.

Since 1899, The Gideons have been distributing Bibles, vowing initially to place a Bible in every hotel room in America, and currently distributing them worldwide at the rate of a million a week. For those traveling generations before radio and television, this was a godsend of literature. Even now, many find occupation for an idle hour in a motel-room Gideon Bible; no doubt some readers find Salvation, and perhaps a few contrarians find Enlightenment. As Nietzsche points out, the drive for first-hand spiritual knowledge, tempered by the deep need for honesty in scholarship, already has brought us a long way.

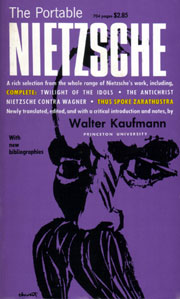

In my truck, for reserve or emergency if I don't have any current reading along, reside a couple of omnibus volumes by Friedrich Nietzsche: The Portable Nietzsche and Basic Writings of Nietzsche — duplicates of my bookshelf copies. These are the Walter Kaufmann translations, with some commentary. The Portable includes the three short hammer-books Twilight of the Idols, The Antichrist, Nietzsche Contra Wagner; and the fabulous Thus Spoke Zarathustra. The Basic Writings includes his first book The Birth of Tragedy, the great flight Beyond Good and Evil, the "natural and experimental history" (to use Francis Bacon's terms) On the Genealogy of Morals, wrap-up books The Case of Wagner and Ecce Homo, and assorted selections.

In my truck, for reserve or emergency if I don't have any current reading along, reside a couple of omnibus volumes by Friedrich Nietzsche: The Portable Nietzsche and Basic Writings of Nietzsche — duplicates of my bookshelf copies. These are the Walter Kaufmann translations, with some commentary. The Portable includes the three short hammer-books Twilight of the Idols, The Antichrist, Nietzsche Contra Wagner; and the fabulous Thus Spoke Zarathustra. The Basic Writings includes his first book The Birth of Tragedy, the great flight Beyond Good and Evil, the "natural and experimental history" (to use Francis Bacon's terms) On the Genealogy of Morals, wrap-up books The Case of Wagner and Ecce Homo, and assorted selections.

Nietzsche is designedly light-hearted but not light-weight philosophy; when one desires the consolations of philosophy, one really should have something first-rate at hand. Don't read these in traffic.

Someday — if literacy is not vanquished by faithful or fraudulent trivialization — when a wrist computer can access the Library of Congress and the British Library, readers will have all of world literature at their fingertips, or wrist-top. This glorious cascade of words and ideas will depend of course on the access link working and the battery holding out — especially when one needs material for emergency reading. The risk of word-drought and book-famine will be vanquished; at hand will be a printed plenitude that Pharaoh's traders and engineers could not have imagined.

© 2004 Robert Wilfred Franson

R. C. Benchley's

Open Bookcases

Mr. Bookish Blows His Horn

The Call to Reading

| Troynovant, or Renewing Troy: | New | Contents | |||

| recurrent inspiration | Recent Updates | |||

|

www.Troynovant.com |

||||

|

Essays:

A-B

C-F

G-L

M-R

S-Z

|

||||

| Personae | Strata | Topography | |

|

|||