Switchboard Girls with Gas Masks

Calm and Secret Heroism

Secret and determined

The Cabinet War Rooms, in a basement under a big Whitehall office building in London, served as Great Britain's secret operational headquarters during World War II. Several hundred men and women, military and civilian, worked there throughout the war, while the city stood up to the Luftwaffe's Blitz and the later V-1 bomb and V-2 rocket attacks which killed 65,000 people in London.

Prime Minister Winston S. Churchill spent much time underground in the Cabinet War Rooms, along with key military, naval, and air officers. They were supported by staff who mapped such critical items as the status of the shipping losses to U-Boats, kept the headquarters in telephonic communication with forces around the world, and so on. Many of the ranking personnel and Churchill's own staff slept on spartan bunks in small rooms; Churchill himself slept there occasionally. Secretaries and other lesser functionaries slept in the "Dock", a low-ceilinged sub-basement space under the War Rooms. No windows, no flush toilets, no fancy anything. Just quiet determination to win the war that had to be won.

Today this Whitehall basement is an excellent museum, divided into two areas. The first is a section of the Cabinet War Rooms themselves: some rooms just as they were when locked up in 1945, and some carefully restored to their functional wartime furnishings and appearance.

The other museum section spreads out Churchill's long and amazing career, much of it devoted to public service: in the course of his life (1874-1965) he was a cavalry officer; a war correspondent; in the Western Front trenches in Belgium; and held almost every high office in the British Government. There are lots of exhibits and physical souvenirs of his life. Well worth viewing and appreciating, for if there is one man in the Twentieth Century without whom we might not be here today, that is Churchill. If the fate of freedom turned then on a hinge of resolve, it was Churchill who turned it. See for instance, John Lukacs' Five Days in London, May 1940.

For me, one of the most emotionally moving aspects of the Cabinet War Rooms exhibit is among its least glamorous functions: the telephone switchboard in a room by itself, small enough to be operated by one young woman at a time in shifts around the clock. Officers in the next room with their banks of phones depended on the steady competence of the switchboard girls to connect them to the world. At the juncture of British war communications, these switchboard operators could have little acclaim out-of-doors: what they did was secret; even where they worked didn't exist to the public. A uniformed soldier on leave from fighting Rommel in North Africa, or a courier from the Western Pacific, or a sailor between convoys to Russia — these might enjoy well-earned public appreciation for their risk-taking and their bravery.

The switchboard girls worked in secret, never mentioning their war work even to their families. Some didn't speak about it until decades later.

In a way, though, down in their cramped basement room they were expected to stand firm in the front lines even more than most residents and workers in London had to, under the aerial bombardments. The operator on duty had at hand a special gas mask designed to allow her to stay at her post, listening and talking and making connections, in case of gas attack.

In a way, though, down in their cramped basement room they were expected to stand firm in the front lines even more than most residents and workers in London had to, under the aerial bombardments. The operator on duty had at hand a special gas mask designed to allow her to stay at her post, listening and talking and making connections, in case of gas attack.

Let me pause here. Poison gas is thoroughly nasty. Depending on the type, it painfully burns the lungs and soft tissues, blisters exposed skin, and so on. It may blind or kill, and within seconds. The only reason the Nazis didn't release any on the battlefield or against enemy cities was that Adolf Hitler, in the previous war, while a soldier at the Front had been gassed seriously enough to land in hospital. I've been in simulated gas-attack and related training in the U.S. Army, and even briefly breathing poison gas is not pleasant. Just breathing clean air through a gas mask feels to me as though I'm being suffocated.

Visualize these unsung switchboard girls, in the basement along with the rest of the Cabinet War Rooms. Poison gas necessarily is heavier than air, or it would waft into the stratosphere. It gathers in hollows, shell craters, valleys, basements.

The operators worked their shifts in that windowless room, around the clock, day in and day out. A gas mask customized for them waited within reach. They remained faithful to their task, working in secret, until the war was won.

© 2012 Robert Wilfred Franson

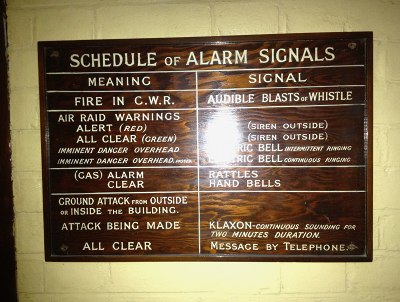

wall sign, above:

Schedule of Alarm Signals

Cabinet War Rooms

photo by RWF

Imperial War Museums' site for

Churchill War Rooms, London:

including the Cabinet War Rooms

& the interactive Churchill Museum

Britain at Troynovant

Britain, British Empire, Commonwealth

Winston S. Churchill at Troynovant

ComWeb at Troynovant

mail & communications,

codes & ciphers, computing,

networks, robots, the Web

Warfare at Troynovant

war, general weaponry,

& philosophy of war

| Troynovant, or Renewing Troy: | New | Contents | |||

| recurrent inspiration | Recent Updates | |||

|

www.Troynovant.com |

||||

|

Essays:

A-B

C-F

G-L

M-R

S-Z

|

||||

| Personae | Strata | Topography | |

|

|||