Will Technology Force Us to Choose

Between Privacy and Freedom?

by David Brin

Addison-Wesley: Reading, Massachusetts, 1998

378 pages

The Transparent Society would be more striking if it were less timely — and if it were more topically focused. As it is, I find the book both thought-provoking and frustrating. Nevertheless not only do my thoughts keep recurring to David Brin's proposal, but I suggest it to others as a disturbing and contrarian point of view.

Brin is swimming against a strong tide here: he advocates openness and transparency rather than privacy and secrecy. He points out that as individuals and members of diverse interest groups, we tend to value privacy and secrecy for us, but deprecate them for the other guys, who should be forced to be open and above-board. Some of Brin's examples:

- Citizens don't think government or big business should be able to pry into their affairs, but value truth in politics and advertising;

- Businesses don't want their negotiations or financial innards made public, but need consumer information;

- Government agencies require secrecy to assure our security, but need wiretapping to be able to ferret out crooks, spies, and saboteurs;

— and so on.

So whoever we are, we seem to have a lot to lose and to gain in the struggle between secrecy and privacy on one hand, and transparency, visibility, openness on the other. Brin's answer is reciprocal transparency. He considers that accountability, which requires openness, is a requisite of constitutional government and in fact is a prime virtue of the West. (He says neo-West, an inharmonious neologism which obscures more than helps.)

I have a great deal of sympathy for Brin's thesis. Accountability looks like a critical underpinning of free institutions, and a key feature of any open society. Tyrannies, by contrast, require secret police to enforce obedience, and even gigantic crimes may be hidden.

David Brin is modest, and engagingly open to criticism. He disavows attempting the philosophical depth of one of his key inspirations, Karl Popper's important The Open Society and Its Enemies (1944). The Transparent Society is dedicated:

To Popper, Pericles, Franklin, and countless others who helped fight for an open society... and to their heirs who have enough courage to stand in the light and live unmasked.

Brin cares about science, free markets, and democracy, and is deeply concerned to find solutions to the challenges of our time and of the future. He proclaims pragmatism, but his ethical earnestness shines through. To sidestep the conflicting claims for openness versus privacy, Brin tries to make falsifiable statements, a scientist's approach which Popper would approve: not exhortations, but pragmatic solutions that a free society can try out.

And Brin says we will be trying out many new solutions in this conflict of openness versus secrecy. We have been in this struggle throughout history, but the technological pace is pushing the conflict toward unprecedented extremes. Encryption and ultra-miniature cameras pose the challenges on which Brin concentrates.

Brin spends perhaps too much time in The Transparent Society on current Internet technologies and debates, particularly on cryptography as applied to Internet mail and financial transactions. He also is distracted by the concept of elective affinities via the Internet, new friends far away.

In an attempt to be both modest and open, Brin invites tag commentary on his own writing, without seeming to realize that such online, in-line commentary easily shades into misdirection or substitution by dishonest web-browser software. I'll give some examples: where the creator's text mentions America, the browser adds "helpful links" to anti-American groups and Mindwash Soap; where the original text has freedom, the browser program substitutes foolishness, etc. I think that in the names of advertising and helpfulness, such doublespeak is a perfect Big Brother override of open communications. Brin should condemn this, not welcome it.

Brin discusses the seesaw battle of encryption and decryption; sometimes secrecy is stronger, sometimes code-breaking. I don't think this is a matter for pessimism or optimism, but rather just awareness of change, annoying and disruptive as such change may be. Like offense and defense — weaponry versus fortification — there may be temporary resting points of stability where one side is ahead, encryption or decryption; but I see no obvious stopping point. James Schmitz's science-fictional futures, including "Agent of Vega" and the Federation of the Hub series, especially its subset Telzey Amberdon series, illustrate beautifully how such seesawing between privacy and transparency, as between weaponry and shielding, may develop in the far future. See my Demigoddess of the Mind: James H. Schmitz's heroine Telzey Amberdon.

But are encryption and code-breaking, even privacy of our records versus prying into them, the most critical issue? I'd say not; our cherished mail and financial records, even medical records, are mere electronic paperwork or bookkeeping. They may be embarrassing or incriminating, but they are extrinsic. Snooping them involves intercepting communications or prying into the storage-banks of communications, whether electronic, paper, or clay tablet. Mail and records are paper trails, they are not ourselves, nor our actions.

Moving on from code-breaking, Brin postulates ultra-miniature flying video cameras that can read our mail over our shoulders before we encrypt it; in fact, they can photograph our much-vaunted encryption passwords themselves, compromising all mail or records using that code. Brin anticipates that gnat-sized cameras may watch our lives at any time, in any detail, and convey all this to strangers. They don't merely read our mail, they watch us.

Do we care? Should we care?

To me this locust-plague of remote cameras poses a far greater challenge than privacy of mail or records. I believe that portable or remote cameras are far more intrusive than fancy wiretaps or mail-readers — and thus more richly rewarding to deploy.

Ubiquitous cameras, remote sensors, spy-rays, even clairvoyance, are common ideas in science fiction since the 1940s. I think these scenarios show that the seesaw between offensive weaponry and defensive fortification is likely to continue, in this particular realm of vision versus opaqueness — no matter how tiny or numerous the cameras.

Brin doesn't want the super-vision in the hands only of the powerful. Else they will keep their secrets, avoid reciprocal transparency and thus avoid accountability. Police and henchmen will spy on the peasantry, who will have no privacy and no recourse.

In other words, Brin says that for citizens to avoid becoming serfs, the citizens need to be able to observe the powerful. Without transparency the powerful cannot be held accountable.

Well and good. Campaign financing will be visible, and there will be no back-room deals that the citizenry cannot discover. — But the citizens' secret ballot also will vanish. Cameras will view your every vote, for anyone to see who is curious. Pressured votes may replace private votes as well as fraudulent counting. Is that a desirable consequence?

As visual transparency becomes radically cheap and easy, I foresee that countermeasures for privacy as well as secrecy will be in increasing demand: Are swarms of gnat-cameras bugging you? The walls of your house have turned to glass and your windows can't be closed? For a small fee, we'll spray the walls with spy-ray-proof paint, and station camera-bug-zappers at every window. Bring back your privacy — you deserve it!

But what if the visibility / privacy seesaw does stop decisively at the transparency side? If not perfectly winning over old-fashioned privacy, at least overwhelming it, as Brin expects and approves. Brin suggests that we may need to cross a transparency threshold of ubiquity and acceptance to make an open society function, and stay free.

Let's speculate that transparency wins outright. I wonder how much transparency should we future stars of stage and screen look forward to?

"Is it true that God is present everywhere?" a little girl asked her mother.

"I think that's indecent." — a hint for philosophers.

Friedrich Nietzsche

Preface for the Second Edition, section 4

The Gay Science (1882, 1887)

translated by Walter Kaufmann

Threshold may not begin to describe the tremendous changes that I can imagine flowing from transparency that is complete or almost so. There are vaster consequences even than Brin's honest citizens and accountable government. I suggest that the implicit larger question is whether we are approaching a transparency singularity phenomenon (to adapt an idea of Vernor Vinge's), a barrier of change so pervasive that ironically we cannot see beyond it, and it is difficult even to imagine the transformed nature of such a thoroughly transparent society.

Can voyeurism be defined as a crime when everyone is encouraged to be a part-time global-village snoop, as Brin proposes — albeit with eyes politely averted from "private" goings-on? — I wonder if we will cease to care who watches? Or will personal voyeur television far surpass webcams, earning fortunes for the networks with the best-placed virtual intruders?

Can stalking be defined as a crime when following people via remote cameras is a constant activity of millions, as Brin advocates? — But how can you differentiate stalkers from other global-village snoops who just happen to be concerned with your lonely welfare on that dark street?

Brin suggests hand-held camera-transmitters as a substitute for weapons, an open and safe deterrent. — Well, the forensic detectives, the prosecuting attorney, and your insurance company will be grateful.

But I suggest we may see an increase in true-crime living theater, with grand-standing rapists, murderers, even mass-murderers eager to perform on-camera for the world. Attractive and famous people too often are targeted now for private and secret crimes. Some criminals crave the publicity that today's after-the-fact exposure gives them. So put their crimes on camera, maybe broadcast them in real-time as they happen. Will the attractive and famous be rated as even better targets, photogenic victims for a world-wide audience for true-crime living theater?

Let's pursue the question of crime before we go on with the concept of complete transparency. I'll take a hard case, apply Brin's transparency, and see what we get. I'll choose a slice of real history and add ultra-miniature remote cameras.

Would increased visibility have deterred Adolf Hitler? The Nazis were secretive about many of their crimes, the mass death-camps and the slave labor. But would transparency have deterred the Nazi leadership at any stage from either their social goals or their war aims? Let's drop virtual cameras into a few points on that timeline.

1920s ... Early in his political career Hitler tried a conspiratorial coup, the Beer Hall Putsch of 1923 in Munich. While in prison following its ignominious failure, Hitler wrote Mein Kampf, in which he laid out many goals, some explicit, and others implicitly required to reverse the social wrongs he claimed to see. Nazi Party members were required to buy (if not read) his book, and it was a big seller. Combined with his readily available speeches to public and Party as the Nazis increasingly won elections, his plans became clear enough to many. — Not despite this considerable degree of transparency, but because of it, Hitler gained control of the German government through lawful means in 1933.

1930s ... When the out-of-power Winston Churchill pointed out to Britain the dangers of Nazi proclamations combined with their rearmament of Germany, he was called a war-monger by those who did not care to see.

1940s ... Assume there are cameras and viewscreens inside the walls of the Warsaw Ghetto in 1942, as well as inside Treblinka, a major Nazi death-camp. A train leaves Warsaw daily with thousands of Jews; upon arrival at Treblinka they are murdered. The horrified ghetto inmates in Warsaw see via remote cameras from Treblinka what is happening to the first train-fulls of victims, but what should they do? They have virtually no weapons, and the entire area is controlled by the Wehrmacht and the SS.

Outside help? In America, Britain, and Russia, the Allies also watch Treblinka via remote cameras. American and British power does not yet have command of the air over the Reich and its puppet General Government of Poland; on the ground, Soviet armies still are far to the East. So in plain view, three-quarters of a million Jews are being murdered.

In 1943 the remnants of the Warsaw Ghetto did rise bravely, with pitifully few weapons, against the Wehrmacht; and were defeated. Would they have fought sooner, given more transparency? Of course. — I think they would rather have had weapons than cameras.

Now, back to the promise and threat of complete transparency. Companion technologies to those which give us increasing transparency also give us increasing recordability. Brin points out many benefits of accountability that come with transparency, as well as some liabilities. Many of these will be after-the-fact as we view older records of events.

But recordability gives us another dimension. I suggest that far more emphasis on accountability over time is needed. This perpetual transparency will provide a social shock of tremendous magnitude. Many people are comfortable with the idea of God looking over their shoulder, because they trust their God not only to be just and merciful, but to keep their affairs private.

I emphasize that with digital recording becoming cheaper and cheaper, the spy-cameras' observations become not only public but permanent. If love-making with spy-cameras like flies on the wall seems awkward, consider that all sights and sounds also are being recorded for viewing ten or twenty years later — time-binding with a vengeance. This certainly will add a new dimension to courtship.

This is just part of the transparency singularity I suggest above.

Brin takes up an old idea for opening corporate books to employees and the public. Business negotiations may benefit by openness. — But how about laboratories and workbenches, before work reaches a stage when patents can be applied for? If neither patent nor trade-secret protection is available, what price research and development?

Certainly the publishing of secret diplomatic and other archives after the Tsarist collapse and again after the Soviet collapse has opened much international history to the world, as well as Russian history to Russians themselves. Even relatively open American and British administrations rate a lot of their own clandestine history as worth concealing long after the battle's lost and won.

Neither a suspicious nor conspiratorial type himself, Brin dislikes the idea of conspiracies — groups of people with secret agendas to achieve their purposes. He refers to the Zapruder film of the assassination of President Kennedy in 1963, but despite this visual record that plainly contradicts the government's official Warren Report, and all the live witnesses and the mass of additional evidence that also contradict the report, he does not allow that there was conspiracy in the assassination, nor government-agency involvement in a cover-up after the fact. He characterizes more recent skulduggery as clear as day; all is above-board, no one in the American government could have a private agenda. — But if our good nature will lead us to trust governmental actions no matter how convoluted and begging for honest investigation, why bother to watch? Just let the good times roll.

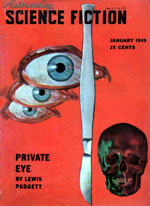

Can you commit a crime with science's Recording Angel watching you — and get away with it, if you plan carefully enough? The novelet "Private Eye", bylined Lewis Padgett (a pseudonym of Henry Kuttner and Catherine L. Moore), was published in Astounding Science Fiction in January 1949. As I read The Transparent Society, I thought of "Private Eye" and expected Brin to mention the neat psychological whodunit which is on precisely this subject. Brin ignores it, although he does refer to many other science fiction stories and authors, some not too related to his topic — for instance, to attack Campbell's and Heinlein's claims for the virtues of individual self-defense.

Can you commit a crime with science's Recording Angel watching you — and get away with it, if you plan carefully enough? The novelet "Private Eye", bylined Lewis Padgett (a pseudonym of Henry Kuttner and Catherine L. Moore), was published in Astounding Science Fiction in January 1949. As I read The Transparent Society, I thought of "Private Eye" and expected Brin to mention the neat psychological whodunit which is on precisely this subject. Brin ignores it, although he does refer to many other science fiction stories and authors, some not too related to his topic — for instance, to attack Campbell's and Heinlein's claims for the virtues of individual self-defense.

I suspect Brin does not get into "Private Eye" because it could lead his thesis too far afield. But to me this is the shocking bright sun of transparency glimmering on the horizon: not encryption of mail and finances, but the eye and ear that see and hear all, and never forget.

A favorite idea of Brin's put forth here is that some people function as cells in the immune system of a society. They fiercely guard openness and freedom, at least within their areas of concern. Since there are many of these individuals with myriad viewpoints, a healthy society will possess lots of watchful eyes, individuals and organizations ranging from the Electronic Frontier Foundation to the Federal Bureau of Investigation. The Freedom of Information Act is an example of a free society attempting to apply such openness to its government servants; organizations such as Judicial Watch strive to hold the American government to this standard. Brin takes pains to point out that there are many kinds of enemies; a complex society will want a wide range of people on the lookout.

These watchful folks will function best when society is open and transparent. High crimes and misdemeanors will be seen, and nipped in the bud. In the Lensman series of science fiction novels that began to appear in 1937, Edward E. Smith postulated that advancing civilization would require such heroes, a hardy and trustworthy band fulfilling this policing function on a grand scale. Each Lensman would need what is essentially clairvoyance and telepathy — as well as being absolutely incorruptible and a dead shot. The Lensmen embody perception, law, and virtue.

Not having Lensmen, can we do it ourselves? What kind of societal mechanisms, what sort of ethical model, do we want to help us manage the hordes of ultra-miniature cameras? A strong secretive clamp-down, or a level viewing field for all? As Brin points out, the cameras already are arriving.

I wonder, will universal glass houses stop stone-throwing?

© 2001 Robert Wilfred Franson

SF & ALC critiqued this review;

WRF strongly appreciated the book.

Astounding January 1949 cover

by Hubert Rogers

David Brin's website section

on transparency, security, privacy, & openness

Cameras & citizen-watchers on the Texas-Mexico border:

Texas Taking Charge

an excerpt from Sylvia Longmire's

Border Insecurity:

Why Big Money, Fences, and Drones Aren’t Making Us Safer

Big Public Is Watching You

Transparency versus Security

Do You Wish to Read My Mind?

Mind Encryption is Here!

ComWeb at Troynovant

mail & communications,

codes & ciphers, computing,

networks, robots, the Web

Constitution at Troynovant

American founding documents,

Declaration of Independence

& U.S. Constitution

Utopia at Troynovant

utopia in power, or dystopia

| Troynovant, or Renewing Troy: | New | Contents | |||

| recurrent inspiration | Recent Updates | |||

|

www.Troynovant.com |

||||

|

Reviews |

||||

| Personae | Strata | Topography |

|

|||