The Annotated Sherlock Holmes

by Arthur Conan Doyle

edited by William S. Baring-Gould

Clarkson N. Potter: New York, 1967;

2 volumes: 691 & 824 pages

For Sherlock Holmes this is always the edition

The Annotated Sherlock Holmes is a full compilation, wonderfully loaded with extras for best enjoying Sherlock Holmes stories in their rich settings. The adventures are centered in huge and complex late-Victorian London and its environs, and range from affairs of state to humble mischances and odd disappearances, with related action from America to Afghanistan. Because of the British Empire's global reach, and so many new and strange people, customs, and creatures making their first impact on Western awareness in the Nineteenth Century, Doyle was able to suffuse many of his stories with a sense of new wonders from previously dark corners of the world.

The large-page, two-column format used in The Annotated Sherlock Holmes places the story text in the inner column of each page, and extensive notes and period illustrations in the outer column. This does not aspire to the grandeur of the multi-volume Interpreter's Bible, but the effect on enjoyability and even readability is more striking. Indeed, there is something Talmudic about reading the notes, many taken from The Baker Street Journal and other high-streets and by-ways of the Holmes experts, as they argue with each other's interpretations of dates, locations, genealogies, and so on. Facts and fancies of plot and technical details come in for a lot of cross-fire from the likes of Anthony Boucher, Christopher Morley, Dorothy Sayers, and other aficionados. But it's in good fun, and enlightening as well as amusing.

You can read the stories straight through smoothly, but there is much practical help for the reader when and if you want it. — We are given illustrations and explanations of odd or merely obsolete artifacts. Foreign phrases are translated. A number of detail maps help our close-in orientation, with endpaper maps of London's neighborhoods and a two-page map of England indicating pertinent locales. If you have tried to employ the famous cipher in "The Dancing Men", it's useful to know about the error persisting in editions from the Strand Magazine onward.

You can read the stories straight through smoothly, but there is much practical help for the reader when and if you want it. — We are given illustrations and explanations of odd or merely obsolete artifacts. Foreign phrases are translated. A number of detail maps help our close-in orientation, with endpaper maps of London's neighborhoods and a two-page map of England indicating pertinent locales. If you have tried to employ the famous cipher in "The Dancing Men", it's useful to know about the error persisting in editions from the Strand Magazine onward.

The Annotated Sherlock Holmes has many fine atmospheric character and scene illustrations, all black-and-white , from the original appearances of the stories in the Strand Magazine (in England) and McClure's Magazine (in America); and photos and engravings. There is background on the artists who contributed much to our visual image of Sherlock Holmes, including stage and screen performers.

All of the sixty canonical stories are included, including the four short novels: A Study in Scarlet, The Valley of Fear, The Sign of the Four, The Hound of the Baskervilles. The first two Holmes stories to appear, A Study in Scarlet and The Sign of the Four, did not make much impact at first:

I was charmed to discover here that it was "A Scandal in Bohemia", always one of my favorites, that led the breakthrough:... the bombshell that was Holmes was not to explode until Conan Doyle conceived the then brand new (in England) idea of writing a series of short stories around one central character.

When "A Scandal in Bohemia" appeared in the July, 1891, issue of the Strand, Holmes did at last blaze into popularity, and by October 14th of that year Conan Doyle could write to his mother that his publishers were "imploring him to continue Holmes."

In addition we glimpse such oddities as "The Giant Rat of Sumatra", which Doyle early on decided was more distasteful than entertaining, and most subsequent compilers followed his lead. We do not, however, get to read "The Papers of Ex-President Murillo", to name one of sundry tantalizing adventures which may be lost permanently. — Not unlike Doyle's first novel which was lost in the mails (not about Sherlock Holmes, and not redone by Doyle); or (among too many others) T.E. Lawrence's original manuscript of Seven Pillars of Wisdom, which Lawrence left on a train and never saw again (he rewrote it from memory).

In addition we glimpse such oddities as "The Giant Rat of Sumatra", which Doyle early on decided was more distasteful than entertaining, and most subsequent compilers followed his lead. We do not, however, get to read "The Papers of Ex-President Murillo", to name one of sundry tantalizing adventures which may be lost permanently. — Not unlike Doyle's first novel which was lost in the mails (not about Sherlock Holmes, and not redone by Doyle); or (among too many others) T.E. Lawrence's original manuscript of Seven Pillars of Wisdom, which Lawrence left on a train and never saw again (he rewrote it from memory).

The stories are arranged sensibly here, in chronological order of the adventures themselves. Like many series authors, Doyle did not write Sherlock Holmes stories in the order in which the events occurred. Baring-Gould and his fellow experts apply considerable ingenuity to work out the dates of the adventures, mostly in the 1880s and 1890s. And exactly so, down to the day of the week, often based on collating in-story references with external information such as the official weather and sunrise-sunset times.

In the over 1500 pages of The Annotated Sherlock Holmes are over a hundred pages of introductory material, informative and entertaining in its own right. (The publisher, Clarkson N. Potter, begins numbering text pages on Page 1, an uncommon practice we commend to other print publishers.) There is interstitial discussion amounting to some forty pages, on topics ranging from poisonous snakes to chronological disputes.

Two of these analyses are:

- The situation of Holmes after his use of ju-jitsu at the Reichenbach Falls disappearance, perhaps including visits to Lhassa, Mecca, and Khartoum before Watson's reunion with Holmes as a disguised bookseller in Kensington in 1894;

— and — - Dr. Watson's wounding on Army service in Afghanistan in 1880, described with apparent contradiction in different stories.

Taken together, these analyses remind me of the President John F. Kennedy assassination knottedness, the döppelganger travels of Lee Harvey Oswald and the "magic bullet" theory for Dallas, November 1963.

On Watson's wounding:

Dr. Sovine suggests that "the Jezail bullet struck Dr. Watson just above and missing the left clavicle, while he was bent over a wounded patient; that it grazed the left sub-clavian artery and shattered the left scapula, then ricocheted, passing to the left and downward, describing a spiral curve deep under the skin of the chest and abdomen, thence downward into the left leg, coming to rest in the calf muscles. ... The shoulder was still bothersome in 1881, but healed and forgotten by the fall of 1887; while the bullet in the leg would be forgotten most of the time, but quite painful during weather changes. ... Apparently when the weather was decent [Watson's] leg was quite serviceable."

This is also the view of Mr. R. M. McLaren ("Doctor Watson — Punter or Speculator?"): "The wound sustained by Watson in Afghanistan was an extraordinary one, the bullet having entered his shoulder and emerged from his leg..."

The views expressed above may, perhaps, be summed up as the One Singular Wound at Maiwand School.

But we know that nature never imitates art, nor is anyone ever inspired by fiction. Anyway, all this fact and fancy is in addition to the outer-columnar notes. (Those who would delve still deeper into these mysteries of the past may conveniently start at Sherlockian.net or the Sherlock Homes Society of London — but once afoot along Victorian paths you risk becoming entranced and mazed, indeed in peril of returning unaffected.) The Contents pages of The Annotated Sherlock Holmes usefully include for each story a sentence or phrase to jog the memory or incite the interest of the reader.

A prime virtue of these pioneering detective stories is that they are about exotic challenges of detection, not simply yet another murder to which a detective is assigned. Some are not crimes at all — but they are interesting puzzles. Holmes is a supreme master of disguise as well as detection; these two arts or sciences are often in opposition, occasionally in conjunction. In "The Science of Deduction", Chapter 2 of A Study in Scarlet, Watson reads an anonymous article (he doesn't yet know it's by Sherlock Holmes) that first lays out for us detection as a system:

Its somewhat ambitious title was The Book of Life, and it attempted to show how much an observant man might learn by an accurate and systematic examination of all that came in his way. It struck me as being a remarkable mixture of shrewdness and of absurdity. The reasoning was close and intense, but the deductions appeared to me to be far-fetched and exaggerated. The writer claimed by a momentary expression, a twitch of a muscle or a glance of an eye, to fathom a man's inmost thoughts. Deceit, according to him, was an impossibility in the case of one trained to observation and analysis. His conclusions were as infallible as so many propositions of Euclid. So startling would his results appear to the uninitiated that until they learned the processes by which he had arrived at them they might well consider him as a necromancer.

'From a drop of water,' said the writer, 'a logician could infer the possibility of an Atlantic or a Niagara without having seen or heard of one or the other. So all life is a great chain, the nature of which is known whenever we are shown a single link of it.'

From a drop of water — To take the last droplet first, consider the progress of biochemistry in crime-solving, where analysis of hair and skin fragments down to the DNA level has contributed amazingly to otherwise unsolvable crimes. Is there a limit here, or a point of vanishing returns? We're farther from such a limit than we would have thought in the heyday of Holmes and Watson. To visualize the universe via a minute portion of it is a philosophical puzzle, pushed far indeed in the science-fictional background to Edward E. Smith's Lensman novels.

Fathom a man's inmost thoughts — Well, that would take telepathy; but by the time we can do it, we mayn't call it telepathy any more, but articulated brain-wave resonance or something like that.

Deceit ... an impossibility — I certainly thought this a pardonable exaggeration for Doyle's fictional purposes. But some years ago I attended two sets of university lectures on mind-brain interactions, by people trained in both medicine and psychology. One of the startling topics was a study of just who could detect liars in the act of lying right in their very faces. Research showed that the general public could guess the truth or falsity of a given arbitrary statement (without context) spoken to them about half the time; in other words, we might as well flip a coin and call it True or False. It was surprising that some specialized professions, folks in the business of interrogation and evaluation, could not do significantly better: judges, policemen, prosecutors, lawyers, psychologists — as far as judging arbitrary statements true or false, as a group they might as well flip coins too.

One group did stand out in this specialized study: the United States Secret Service, those federal agents whose particular duty is guarding the President of the United States. Their ability to recognize lies was notably better than average.

How could that be? Is truth recognition really possible at all, or are the Secret Service agents inspired guessers, chosen for their luckiness (among other sterling qualities)?

The study on lying included filming the participants who were stating the truths and untruths to be identified. Many of the statement-speakers seemed to provide no clues that even a psychologist's eye could detect. But the films, slowed way down and greatly enlarged, showed otherwise. The faces of the speakers, under enhanced filmic scrutiny, revealed tiny movements of the muscles: to this hyperacute scrutiny, the liars' faces betrayed their falsehoods.

So an exceptional person could in fact possess a rare hyperacuity, partly visual, partly trained, and not necessarily entirely conscious, to unravel the minute motions that reveal secrets of a speaker's face, perceivable only by rare individuals, a Secret Service agent, or a Sherlock Holmes.

© 2001 Robert Wilfred Franson

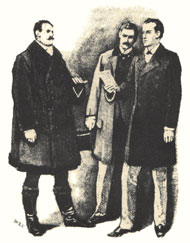

Strand Magazine July 1891

illustration by Sidney Paget for

"A Scandal in Bohemia"

Bookmark by Jennifer M. Franson

on bound volume of Strand Magazine

Detection at Troynovant

solving mysteries; detective agencies

Guise at Troynovant

masks, disguise & camouflage;

roles, acting, reenactment

| Troynovant, or Renewing Troy: | New | Contents | |||

| recurrent inspiration | Recent Updates | |||

|

www.Troynovant.com |

||||

|

Reviews |

||||

| Personae | Strata | Topography |

|

|||