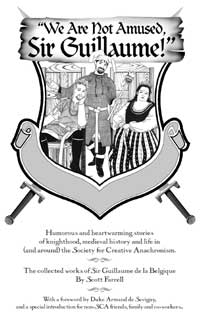

"We Are Not Amused, Sir Guillaume"

The collected writings of

Sir Guillaume de la Belgique

by Scott Farrell

184 pages

The Gothic Revival in your neighborhood park

Scott Farrell's chosen historical persona within the Society for Creative Anachronism is Sir Guillaume (pronounced gee-ome), a medieval Norman knight: an impressive fighter, but of otherwise doubtful repute. The most common weapon of an SCA warrior is a sword made from a heavy stick of rattan wood and wrapped in silver-colored duct tape. This sword is not edged metal, but it hits mighty hard. A knight's home-made armor has to be tough, and so does the knight.

But why would latter-day knights of the SCA have fun with sword-fighting, with medieval costume and armor that are not viewed in a museum case but worn and used in action? It's not combat to the death by any means, but it definitely is combat.

In contrasting the pomp and ceremony and more-personal battle of late Nineteenth Century armies with the gloomy mud and massive death of the First World War's No-Man's-Land, Winston S. Churchill — who knew both at first-hand — said that when the pageantry was taken out of warfare, they took out the best part. The Society for Creative Anachronism manages to restore some of the better aspects of the Middle Ages to our awareness, not only intellectual but tactile and sociable, feasting and costume and dance as well as arts and technologies. Spare-time re-creations not only of knighthood, but all manner of life in the roughly thousand years from the fall of the Roman Empire up to 1600 A.D. A new Gothic Revival in your neighborhood park. This re-creative, participatory experience is the Current Middle Ages, as they call it.

Sir Guillaume after twenty years of not-so-leisure time in the Society for Creative Anachronism knows this lifestyle well. He has served terms as Baron of Calafia and as King of Caid. For an introduction to all this, see his essay on Living in the Current Middle Ages here at Troynovant. With that essay are photos of Sir Guillaume in combat (on the right) at a Crown Tournament; and on the throne, alongside Lady Felinah.

Sir Guillaume after twenty years of not-so-leisure time in the Society for Creative Anachronism knows this lifestyle well. He has served terms as Baron of Calafia and as King of Caid. For an introduction to all this, see his essay on Living in the Current Middle Ages here at Troynovant. With that essay are photos of Sir Guillaume in combat (on the right) at a Crown Tournament; and on the throne, alongside Lady Felinah.

What does all this re-creative, anachronistic experience lead to? In Sir Guillaume's case (a hard case, I grant, even without the chain mail), one writes a long-running column called I Didn't Expect an Inquisition for a regional SCA magazine, The Crown Prints of the Kingdom of Caid.

real, reenacted, and/or wildly imagined

We Are Not Amused, Sir Guillaume consists of some three dozen reprinted and new essays: about the SCA; discourses on medieval history (mostly English and French); and sundry personal and domestic excursions in the Current Middle Ages. There is not only an "Introduction" but a useful "Introduction for Non-SCA Members". Two of the topics are multipart: "The Hundred Years War" (history, more or less) and "An American Knight in England" (a personal visit in search of history). In addition to mangled history, Farrell shares a lot of his own misadventures, many as funny as the Plague, or even funnier.

I have to deplore that herein you may notice a slight, barely perceptible exaggeration or two. As for facts, as sure as the Earth is flat, Farrell's historical research beggars description. There also is humor. Despite the title, you will of course be amused, even if you've never heard of the SCA before. — Although it would help if you've at least heard of history before.

On King Philippe VI of France, from "The Hundred Years War, Part II: Too Much of a Bad Thing":

In consultation with his royal advisors, Philippe concluded that the plague was the result of God's displeasure with him for not collecting enough taxes. He then sent out a number of decrees which raised taxes, lowered wages, restricted travel and cut Medicare. Under these new laws, public morale soared to about the level you might expect. With the populace in a terrified panic and the peasants on the verge of revolt, King Philippe, showing the kind of dignity and grace that modern leaders can only dream of, died.Into the medieval briar patch

Scott Farrell's teenage interest in medieval swordfighting was brought to life by an SCA demonstration at his high school, and reading The Once and Future King. This discovery was more significant than he could have realized at the time. His personal progression via the SCA as told here reminds me of someone who had a somewhat similar lucky chance.

Scott Farrell's teenage interest in medieval swordfighting was brought to life by an SCA demonstration at his high school, and reading The Once and Future King. This discovery was more significant than he could have realized at the time. His personal progression via the SCA as told here reminds me of someone who had a somewhat similar lucky chance.

I'll give an anecdote of my own. One of the very best technical managers I've ever known had an inauspicious start — via the U.S. Marines. I gather that in a youthful excess of energy, and a youthful casualness about staying within the bounds of the law, this young fellow got in trouble. The judge decided that his was an error of youth rather than a flaw of character, and drawing on an excellent tradition, gave the offender a traditional choice to settle him down: Jail — or the Marines. No fool he, the youth chose the Marines.

While in the Marines, in addition to the usual hard training and personal discipline, the young fellow was taught large-computer operations. This set him on a career path that in civilian life went on to programming, systems analysis, and management. He became a fine manager: innovative, empathetic, calm, clear, and balanced.

Has the SCA some virtues in common with the U.S. Marines? I suspect that back in high school, young Scott Farrell, moving beyond the thrill of whacking a schoolmate with a copy of the Iliad, instinctively recognized in the chivalrous warriors of the Society for Creative Anachronism a role model that would be good for him. A real School of Hard Knocks. He plunged in, and perhaps to his surprise, over the years he kept growing within that model:

I ... was just a dumb fighter. My role within the barony was very specialized: I hit people in the head with a stick, and I did it fairly well, thank you. Oh, I would occasionally autocrat a tourney or hold an odd office like captain of archers or knight marshal (both of which, you may note, involve the use of lethal weaponry) but nothing which I considered particularly noteworthy.

So, you can imagine my surprise when [... Talanque, the current Baron] came to me and said ... he wanted me and Felinah to become Baron and Baroness when he stepped down.

True to form for We Are Not Amused, Sir Guillaume, his account of office-holding in the SCA combines humor and seriousness in good proportion. Sometimes even mundane ("real-world") management rubs up against a tendency to think historically:

After many years in the Society, I sometimes find myself in strange situations and wonder, "How would a normal person react to this?" For example, I'm not sure if a typical employee would, in the middle of a monthly safety committee meeting at work, begin to contemplate how a modern office structure compares to the organization of King Stephen's army at the Battle of Shrewsbury.

Well, sure; doesn't everyone? When in such situations myself, I'm likely to draw comparisons with the American Civil War — with political generals, with idealistic hopes and bravery and great blunders. But I'm fairly modern.

To return to schooling, Farrell castigates politically-correct school boards that ban books such as those about King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table as:

... off limits because they encourage violence as a method of conflict resolution, and glorify dealings in the occult. ...

Just imagine the difference your gift [of such books to young people] might make in their lives. Just imagine where they might go, guided by the inspiration of these mythic tales. Just imagine one of them sneaking up behind you, looking for a way to put their 500-page copy of the Iliad to use.

Yes, long before becoming Sir Guillaume, or discovering the fulfillment of historical reenactment, the student Scott Farrell had a certain feeling for combining history and combat. He speaks here from experience. — In another essay, he stresses a very serious point:

A story derives its meaning not just from a lack of unpleasantness, but from the values embodied by its characters and the causes they uphold with their actions. Just as the romantic epics of the Middle Ages planted the seeds of chivalry and honor in the minds of young knights, today's entertainment — television, movies, books and computer games — should encourage our children to protect the weak, strive for justice and respect the laws of the land. We can only hope that, in an effort to teach our children not to fight, we don't teach them that nothing is worth fighting for. Chivalric adventures — and Saturday matinees — would never be the same.

To back the philosophical side of his affirmation, I'll invite further speculation along those lines:

Every talent must unfold itself in fighting: that is the command of Hellenic popular pedagogy, whereas modern educators dread nothing more than the unleashing of so-called ambition. ... And just as the youths were educated through contests, their educators were also engaged in contests with each other.Friedrich Nietzsche

"Homer's Contest"

There's a lot of material packed into We Are Not Amused, Sir Guillaume: Kings and Queens and battles in real historical times. Fun with re-creations in the Current Middle Ages. Viking-era practical research, in the back yard, with a battle-axe. Cuisine — high, low, unfortunate, and broadening. Door-opening for modern ladies, and how such petite-gallantry wins no dates in high school. Why Sir Guillaume's chain mail retains smells of English cheese and onions. A half-dozen guys trying to move a boulder with old-time technology.

Despite the jester's cap, there are a number of atmospheric and thoughtful moments in We Are Not Amused, and some very moving ones. (No, not the boulder-moving episode.)

Wearing warrior's helm, royal crown, or jester's cap, Sir Guillaume tells a pretty good tale.

© 2001 Robert Wilfred Franson

For a complete chapter here at Troynovant, see

1066: Changing the English Channel

Scott Farrell develops a more serious approach at

Chivalry Today:

Reimagining the Code of Chivalry

Photos courtesy of

Sir Ryan Greenoak (Ray Ford)

| Troynovant, or Renewing Troy: | New | Contents | |||

| recurrent inspiration | Recent Updates | |||

|

www.Troynovant.com |

||||

|

Reviews |

||||

| Personae | Strata | Topography |

|

|||