1632

by Eric Flint

Baen: New York. 2000

Non-heroes thrust onto a battlefield

Warriors make fine heroes; but what happens to the young, the innocent, the pregnant, in a war-torn country? War often comes to them as well, they are easy targets, they are raped and brutalized and starved and slashed, and they die. Do writers of adventure novels ever think carefully about these non-warriors except as love-interest or decoration or background? Read on.

1632 is a historical alternate-timeline novel, and I think an exceptionally good one. Eric Flint's science-fiction situation here is simple, explained in a two-page Prologue. An artificial spacetime anomaly transposes two spheres on the surface of the Earth, spheres each about six miles in diameter, or six miles across on the ground if you had a straight country road. These spheres — or disks of countryside if you like, with a hemisphere of dirt and rock underneath and a hemisphere of air above — exchange places.

The first of these spheres happens to contain a small coal-mining town in our here and now: Grantville, West Virginia. A typical American country town: the geographic setting and layout of Grantville are based on a real town, Mannington, West Virginia. Family ties and the local branch of the United Mine Workers of America are their community strengths. Michael Stearns, an energetic and engaging fellow and a union negotiator for the local UMWA, is our central protagonist.

In a flash of spatio-temporal shock, "a Ring of Fire", quiet Grantville suddenly is plunked into the province of Thuringia in the middle of Germany — displaced in time as well, to the lovely rural Springtime of 1631, when a hopelessly fragmented Germany is the battleground for the Thirty Years War.

A matching bubble sliced out of Thuringia's forested hills in 1631 appears in West Virginia in our here and now. After the Prologue's explanation, the novel does not concern itself with that side of the equation. But back in 1631, of all times —

This is the terrible era of the wars of the Counter-Reformation. Armies, more or less Protestant versus Catholic, fight across Central Europe, with mercenary bands wreaking random havoc. Cardinal Richelieu, the Holy Roman Emperor, King Gustav II Adolf of Sweden, General Tilly, Count Wallenstein, and a gaggle of German dukes and princes are major players of the time. During the Thirty Years War (1618 - 1648), rulers, countries, and armies can and do change sides without notice.

The King of Sweden, known beyond Sweden and to history as Gustavus Adolphus, is the major historical character in 1632. Other historical persons mentioned above figure in the plot, but it is the Swedish King with his Swedish and Scots chief officers who are important real characters in this novel.

Gustavus Adolphus leads the major Protestant army currently maneuvering and fighting in fragmented Germany; Count Tilly is the general of the major Catholic army.

Magdeburg, the key fortress of the Elbe and one of the wealthiest cities of Germany, was the strategic base coveted by both Gustavus and Tilly. It had, moreover, sullenly resisted the crusading zeal of the Emperor, so that if Gustavus could hold it he would at once justify himself as a Protestant champion.

C.V. Wedgwood

The Thirty Years War

General Tilly's army besieged the walled city of Magdeburg in April 1631. But Gustavus Adolphus had major Protestant allies who were in the way of his army marching to the rescue, and proved obstacles rather than allies; Gustavus could not get to the city. On 20 May 1631 Magdeburg was taken by storm.

This is the Europe of Holy War that little Grantville, West Virginia, is dropped into.

A great pioneering novel in this tradition is Lest Darkness Fall by L. Sprague de Camp (1939), wherein a single man is displaced into the late Roman Empire; can he do anything about it, for himself or for Rome? In 1632, about 3,000 people in Grantville are displaced several centuries. What do they do?

In Robert A. Heinlein's novels, seemingly ordinary men and women find themselves in situations demanding thoughtfulness, flexibility, and heroism; and they cope. Similarly, the new Old World these Grantville folks find themselves in is often confusing and dangerous, yet they cope with it.

Although an exciting flurry of action happens near the start of the novel, for me the plot really begins to take hold at the end of Chapter Three, with the arrival of Rebecca Abrabanel and her father, in a carriage pursued by a band of Tilly's mercenaries. Brilliant and multilingual daughter of a diplomat, member of one of the great Jewish banking families of early modern Europe — with her this mix of West Virginians and Europeans really begins to show its promise. As Nietzsche might say, with Rebecca the human mix becomes exotic, complex, subtle.

Michael Stearns and some of his mine-worker friends have just rescued Rebecca. She's told them they are in Germany, but he doesn't yet believe that the oddly dressed mercenaries could be in the Germany he knows:

A rich diversity of heroinesMichael barked a sudden laugh. "God, the Polizei would round them up in a minute! Germans love their rules and regulations." Another barked laugh."Alles in ordnung!"

Rebecca's own brows were furrowed. "Alles in ordnung?" What is he talking about? Germans are the most unruly and undisciplined people in Europe. Everybody knows it. That was true even before the war. Now —

She shuddered, remembering Magdeburg. That horror had taken place less than a week ago. Thirty thousand people, massacred. Some said it was forty thousand. The entire population of the city, except the young women taken by Tilly's army.

I am going to speak more of the heroines than the heroes of 1632, not because the home-town boys and their local-time enemies and allies aren't interesting in their own right, but because it is the women that loft the plot and the texture of this novel out of the ordinary run of good adventures.

A second heroine is Gretchen Richter, a young Catholic woman dragging along among the camp followers of a detachment of Tilly's mercenaries. She is a survivor in the worst of circumstances: brutally mistreated but still striving to protect her younger siblings and other random victims of the war who, recognizing her character, cling to her. Gretchen is the model of unarmed bravery on a battlefield without boundaries.

An American high-school girl, bouncy cheerleader Julie Sims, is the third heroine we get to know. While a lot of folks in Grantville are hunters, Julie is an Olympic-quality competition target-shooter, recognized as the best shot in the county. If you've ever seen the scores for the best young women in a major rifle-match, you can be very glad that America still produces such real-life marksmen. Annie Oakley is the most famous of the breed, not the last.

In many novels, certainly in most adventure and science fiction novels, women's active participation in the plot is given short shrift (that's the old spelling for short shift, that is, showing her bare legs). But women in 1632 galvanize the plot as well as decorate the scenery. This is important because our perspective of distant heroes tends to be complacently boundaried. In peaceful places in coddled times we yarn of adventure-seekers who explore distant dangers, or fight battles long ago and far away. Jason and Hercules; Achilles and Hector.

A glance now at the really long perspective. Most of history, the immense Pliocene vistas of protohuman living and dying, then the long Pleistocene twilit dawn of humanity, has not been only a struggle of heroes, strong men armed.

In a book on the evolution of the human female form, Elaine Morgan speculates on what happened to our pregnant ancestress, a protohuman gal newly afoot on the dry Pliocene savannah:

The example of MagdeburgThe only thing she had going for her was the fact that she was one of a community, so that if they all ran away together a predator would be satisfied with catching the slowest and the rest would survive a little longer. This wasn't much of an advantage [...] The males, fresh from the trees, wouldn't have yet worked out the baboon strategy of posting fierce male outriders when the herd moved on; and if the predator always ate the slowest of the tribe, the cycle of gestation ensured that the time would soon come when the slowest would be you know who.

What, then, did she do? Did she take a crash course in walking erect, convince some male overnight that he must now be the breadwinner, and back him up by agreeing to go hairless and thus constituting an even more vulnerable and conspicuous target for any passing carnivore? Did she turn into the Naked Ape?

Of course, she did nothing of the kind. There simply wasn't time. In the circumstances there was only one thing she could possibly turn into, and she promptly did it. She turned into a leopard's dinner.

Elaine Morgan

The Descent of Woman

There are no leopards in central Germany. But if ever you wondered what a more recent analogue to such ongoing lack of safety, of fear by day and by night, of all-too-likely death not just for warriors but for the young and innocent and pregnant — look at the landscape of the Thirty Years War. The catastrophe of Magdeburg quickly became infamous throughout Europe, but it was far from alone, and the war was less than half over.

Far into the night the city burnt, and smouldered for three days after, a waste of blackened timber round the lofty gothic cathedral. How it happened no one then knew or has ever learnt. One thing, however, was clear to Tilly and Pappenheim, as they looked at the sulfurous ruin and watched the dreary train of wagons that for fourteen days carried the charred bodies to the river — Magdeburg could no longer feed and shelter either friend or foe.

... Of the thirty thousand inhabitants of Magdeburg about five thousand had survived, and these for the most part women. The soldiers had secured them first, carrying them off to their camp before returning to sack the city.

C.V. Wedgwood

The Thirty Years War

Even our civilized history must include the noncombatants, the physically weaker, the poorly armed. What is the fate of the women with nursing infants; the children; the heavily pregnant women? — Consider the fall of Troy, with murder, rapine, and enslavement. Even more recent history is pocked with awful blemishes. In May 1631, Magdeburg.

With only a tenth the population of Magdeburg, and not even that city's high stone wall, what can 3,000 people of Grantville do in such an environment? Their twin, instinctive decisions are to survive, and to retain their American character as they understand it. Our main protagonist Michael Stearns knows more than a little of the American Revolution, its history and its values, and particularly admires George Washington.

With only a tenth the population of Magdeburg, and not even that city's high stone wall, what can 3,000 people of Grantville do in such an environment? Their twin, instinctive decisions are to survive, and to retain their American character as they understand it. Our main protagonist Michael Stearns knows more than a little of the American Revolution, its history and its values, and particularly admires George Washington.

Remember, in our real world or in a fairly portrayed alternate history, we deal not only with warriors. Grantville is not an Argo filled with Greek heroes of legend sailing into unknown waters. These are regular American folks, with the usual proportion of women and children. A healthy society must cherish and protect its pregnant women, not just cheer its bold fighting men. But is there room for heroines, or must women be either coddled or victims? Is it an accident that the modern West, and American values, have best allowed women, even pregnant women, to defend themselves?

The diversity and balance of characters in 1632 are well handled. The balance repays the effort to create it, although given the chaotic and war-torn setting it must be more explicit in 1632 than for instance in Heinlein's Rocket Ship Galileo. Catholic, Protestant, Jew, believer, unbeliever; German, Swede, Scot, Finn, Spaniard, displaced American. With this balance Flint's goal resembles Heinlein's: a broad and deep vision of what it means to hold American values.

Clausewitz's concepts of the inherent confusion and uncertainty of war, and of what military genius really requires, do not lessen the responsibility of the Grantville folks and their allies (and enemies) to make decisions of value. 1632 faces up to this complexity. The protagonists act with ingrained belief in American values, and as immersion in the Thirty Years War sharpens their understanding, with increasing clarity and firmness.

And the novel finds room for much more. In addition to the excitement of soldiering and diplomacy in 1632, we are given much friendship and affection. There are bits of humor: the question of authorship of Shakespeare's plays; Seventeenth-Century Germans watching a silent film of Buster Keaton; music ranging from the college song "On, Wisconsin" to Alban Berg's Wozzeck. All this grows on re-reading.

1632 also is a very loving book, surprisingly given its setting — but this is deliberate. There is romance here, and love also; happy love-making and even pregnancy. Not many adventure novels think to show that a beloved woman, pregnant, becomes quite as lovely with broad nurturing curves as with her slim embracing curves.

I stint the men in this review, who are thoughtfully various and well-drawn, interesting and likable (or villainous), only so I may draw special attention to the vital women and the values they uphold. Rebecca Abrabanel's brilliant diplomacy and Gretchen Richter's courageous leadership are both mixed strongly with love for the men they find. They are models of feminine bravery in odd and dangerous circumstances.

As for the schoolgirl sharpshooter Julie Sims: on these frightful battlefields of the Thirty Years War, the West Virginians and their German allies rejoice right down to the roots of their hearts that steady Julie and her Remington are on the rampart, or the windowsill, above. With a modern rifle she is an Angel of Death on a battlefield.

The American Revolution was not won nor kept by Virtue Unarmed.

© 2003 Robert Wilfred Franson

Germany at Troynovant

Imperial Germany, Third Reich

Prussia, Bavaria, Austria

history, geography, literature

Romance at Troynovant

dating, romantic love, marriage

Warfare at Troynovant

war, general weaponry,

& philosophy of war

Weapontake at Troynovant

weapons, martial arts;

gun rights, freedom of self-defense

There are a host of sequels to 1632,

most in varying degrees of collaboration.

Gustavus Adolphus

(Gustav II Adolf)

King of Sweden

Wikipedia

City of

Mannington, West Virginia

official site

Mannington, West Virginia

Wikipedia

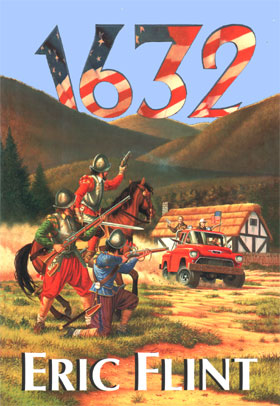

Baen cover (2002 edition), middle left:

by Larry Elmore

| Troynovant, or Renewing Troy: | New | Contents | |||

| recurrent inspiration | Recent Updates | |||

|

www.Troynovant.com |

||||

|

Reviews |

||||

| Personae | Strata | Topography |

|

|||