The Door into Summer

by Robert A. Heinlein

Fantasy and Science Fiction

October, November, & December 1956

Doubleday: New York, 1957

188 pages

A Heinlein Trio

Bicycle-shop engineering

This is a cat story, and a love story, and a time-travel story: all done well. But let me take my own time looping around to them all —

What can one man, or a small team, accomplish today? Does innovation require government or a big corporate conglomerate? Heinlein thinks otherwise, as his narrator Dan Davis muses in The Door into Summer:

What was there small enough for one engineer and not requiring six million man-hours before the first model was on the market? Bicycle-shop engineering with peanuts for capital, the way Ford and the Wright brothers had started — people said those days were gone forever; I didn't believe it.

Certainly Heinlein is, as he says, an individualist and optimist. Or at least, if conditions may require him to be a short-range pessimist, he remains a long-range optimist. Quite aside from any slings and arrows of real contingencies, a novelist's plot pretty well requires a short-range pessimism to power the action. Dan Davis has plenty of setbacks in The Door into Summer, but he's clearly a genius-level engineer in the mold of the Heroic Age of Invention.

When this novel was written, in the mid-1950s, many people were sure those days were gone forever. I'll give just one counter-example from a generation later: the rise of the personal computer, and most particularly Apple Computer. See reviews at Troynovant of Steven Levy's history Insanely Great: The Life and Times of Macintosh, the Computer That Changed Everything; and (a memoir/history by a participant), Andy Hertzfeld's Revolution in the Valley: The Insanely Great Story of How the Mac Was Made.

Yet the emotionally wrenching setbacks in The Door into Summer are with people rather than with gadgets. The plot is a roller-coaster ride and quite suspenseful.

The main setting is Los Angeles and environs, which I happen to know fairly well, and all Heinlein's little details ring true. What is most science-fictional in his contemporary Los Angeles is the future-oriented attitude that Heinlein imparts to his first-person narrator, Dan Davis. Not just vision, but practical design.

Anyone who's been responsible for creating a complex piece of hardware or software with ongoing responsibility for keeping it running has learned the hard way about designing for maintainability. Make your circuits, modules, code, whatever —

... easy to repair. The great shortcoming of most household gadgets was that the better they were and the more they did, the more certain they were to get out of order when you needed them most — and then require an expert at five dollars an hour to make them move again. Then the same thing will happen the following week, if not to the dishwasher, then to the air conditioner ... usually late Saturday night during a snowstorm.

Five dollars an hour ($10,000 per year) was a very good wage rate when the novel was written. Inflation aside, the point remains true. Davis designs for simplicity, modularity, and so on. Think things through as clearly as you can, planning with care to minimize breakdowns and ensure the rare breakdowns are easy to fix.

Davis' sidekick is his tomcat Pete (formally Petronius the Arbiter), who Davis habitually carries in an overnight bag (with top open) and smuggles when necessary into cat-prohibiting places. Pete is a memorable character, and far more significant to the plot than most harmless and decorative cats in stories.

It is Pete who dislikes going out through a wet, weather-hassled doorway until he has looked out of them all, in case one of the other ones is the door into Summer which he can use to stay warm and dry in outdoor felicity. Yet do we not all of us wish for such a door when the coldest contingencies seem to have us surrounded?

An anti-critical interjection: The erudite James Blish, in one of his more waspish moments of critical pedantry, deplores a lapse of Heinlein's Classicism in naming this unharmless but necessary cat Petronius the Arbiter. As not uncommonly with Blish, the several apropos and humorous aspects to this name for this cat in this story all go right past the critic. I don’t know why Blish would complain that Heinlein shouldn't let his character choose for his cat a semi-translation of a classical name. The cat’s judgement and actions are important to the plot, so it wasn’t an idle choice. Damon Knight is much more perceptive on Heinlein in his In Search of Wonder.

Reviewers of The Door into Summer seem to have a hard time describing it without a raft of plot-spoilers (aimed at students swotting up for a book report?), which I will not provide here because I want you to enjoy the novel freshly if you haven't yet read it. Even rereading the book multiple times, though, for me it remains a personal favorite.

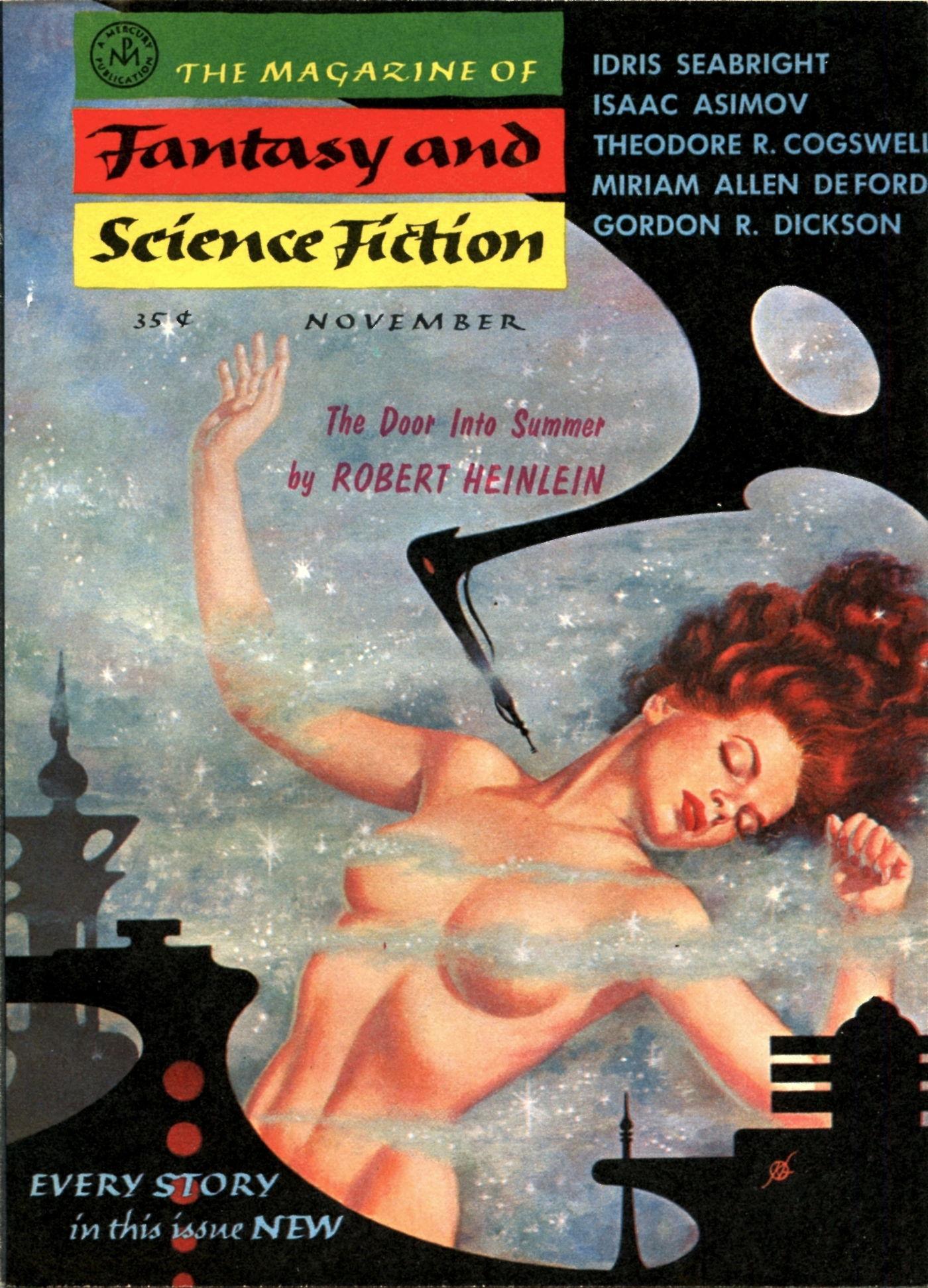

Speaking minimally, The Door into Summer is a time-travel story. But that's not a secret that the Doubleday publishers worry about on their pathetic dust jacket, so no surprise on a first reading unless you happen across a jacket-less hardcover providing only Heinlein's name and an intriguing title. By contrast, the brilliant Fantasy and Science Fiction first-installment cover by Kelly Freas is evocative and beautifully rendered, without plot spoilers.

The Door into Summer involves Cold Sleep, or induced hibernation of folks for medical or other reasons. This explicitly echoes H. G. Wells' When the Sleeper Wakes (1899), but Heinlein's narrative is vastly breezier, entertaining, novelistic. Cold Sleep is central to this plot, whether it seems a summery door or anti-summery; often in SF it is only tangential, for instance in L. Sprague de Camp's "The Stolen Dormouse" (1941) or Heinlein's own Beyond This Horizon (1942). Heinlein effortlessly works in a number of thoughtful, practical details.

Structurally (without the time-travel) the novel reminds me a bit of Ross Lockridge's inventively layered mainstream bestseller, Raintree County. The actual time-travel in The Door into Summer is neatly handled, but not knotted as in Heinlein's "By His Bootstraps" or "All You Zombies". Those stories — to use a phrase Dan Davis uses to describe a prototype household robot — look rather "like a hatrack making love to an octopus". Unlike those, The Door into Summer is a very smooth and clear adventure; a pep-talk for shirtsleeve engineers; an entertaining and insightful contrast of Los Angeles in several periods near to our own, with some surprising details; and a nicely engineered love story to boot. To say nothing (more) of the cat.

A very enjoyable and satisfying novel.

© 2008 Robert Wilfred Franson

Time at Troynovant

temporal philosophy and travel

Coining at Troynovant

quantifying value into commodity;

true coin, false coin, enterprise & economics

Gaius Petronius Arbiter

(circa 27–66 AD)

at Encyclopædia Britannica

Robert A. Heinlein at Troynovant

Romance at Troynovant

dating, romantic love, marriage

magazine cover, bottom:

Fantasy and Science Fiction

October 1956

by Kelly Freas

| Troynovant, or Renewing Troy: | New | Contents | |||

| recurrent inspiration | Recent Updates | |||

|

www.Troynovant.com |

||||

|

Reviews |

||||

| Personae | Strata | Topography |

|

|||