The Future History series

by Robert A. Heinlein

background, annotated story list

chronological by content

Systematic speculation

Robert A. Heinlein's Future History series developed systematically as never before the key vision of the future as complex, evolving, and filled with real people possessing concerns we can recognize and empathize with. Whatever comes will be our future and we will live in it every day.

In the thirty years between the first story's publication and Americans walking on the Moon, many of Heinlein's futuristic concepts became part of the everyday mental furniture of forward-looking people, including the teenagers and scientists and engineers and politicians and military men and voters and taxpayers who made happen the American space program.

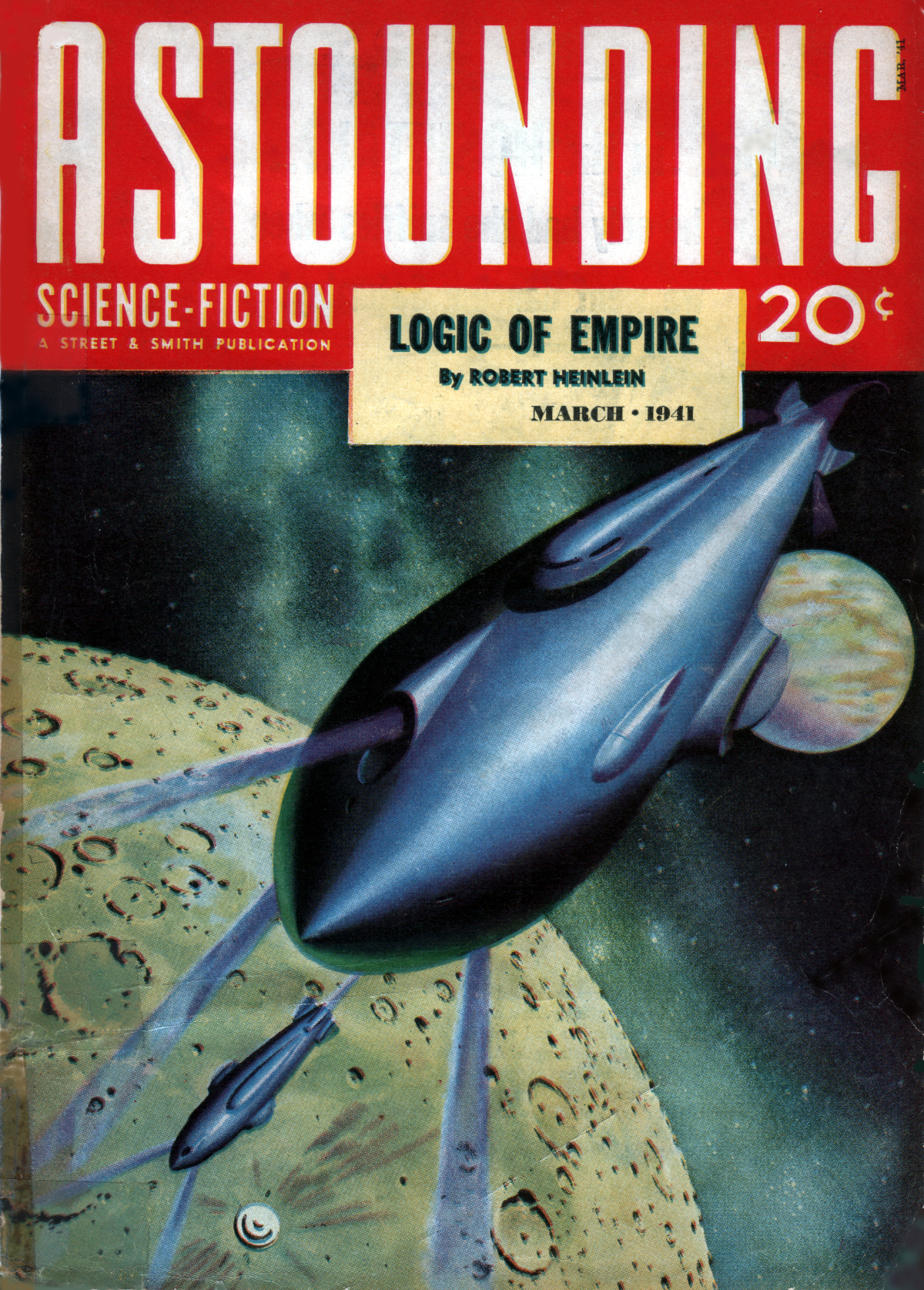

The heart of the Future History series appeared in Astounding Science Fiction from 1939 through 1942, with another clutch of stories mostly in the slick magazines after World War II, 1946 through 1950. A couple of short stories appeared later. The 1941 novel Methuselah's Children was revised and expanded for book publication in 1958, and the longer novel Time Enough for Love appeared in 1973.

The annotated list below shows only stories actually written, in chronological order within the series. For the time-lines of the characters, and Heinlein's fascinating notes for cultural background, turn to a copy of his full Future History chart. Some titles originally charted by Heinlein but never written are set during a period of religious dictatorship; he likely found these plots too negative to enjoy developing.

The first public version of the Future History chart was featured by editor John W. Campbell in Astounding Science Fiction for May 1941. Heinlein was careful to point out that his chart notes were science fictional background, not predictions. But who else in 1941 would have placed a note on a chart marking the 1960s as "The Crazy Years"?

No single form of the series is definitive: hence this list, so you won't inadvertently miss any stories if you want to read them all. Original magazine appearances don't constitute the whole series. Nor do the initial three collected volumes: The Man Who Sold the Moon, The Green Hills of Earth, and Revolt in 2100. Nor do those volumes quite match the stories re-collected, along with the novel Methuselah's Children, in The Past Through Tomorrow. And there is Orphans of the Sky and another separate novel, Time Enough for Love.

As he wrote more stories into the Future History series, Heinlein revised the Future History chart. After the first printed version in Astounding, May 1941, the first collections updated the chart in the early 1950s; finally, the big collection The Past Through Tomorrow printed the chart as he saw it in 1967. The hardcover edition of the latter slips the chart in toward the end, pages 530-531, hidden near the beginning of the included Methuselah's Children. The chart is referred to in Damon Knight's neat alternate-history Introduction but not listed in the Contents.

As he wrote more stories into the Future History series, Heinlein revised the Future History chart. After the first printed version in Astounding, May 1941, the first collections updated the chart in the early 1950s; finally, the big collection The Past Through Tomorrow printed the chart as he saw it in 1967. The hardcover edition of the latter slips the chart in toward the end, pages 530-531, hidden near the beginning of the included Methuselah's Children. The chart is referred to in Damon Knight's neat alternate-history Introduction but not listed in the Contents.

Other novels such as Space Cadet briefly refer to characters in the Future History. As a curious teenager I wrote to Robert A. Heinlein asking him if he would call these part of the Future History; he replied politely via postcard that they were not within the series. So at most they are peripheral with a few congruent touches; at Troynovant we follow standard practice and treat these as entirely standalone.

The annotated list below — like the general Troynovant indexes — for the sake of readability ignores Heinlein's quotation marks within actual titles. As mentioned above, my list does not attempt to indicate the overlapping time-lines of people, events, and technologies in the Future History chart(s). Original publication years are shown on the right. My comments are below each title. All stories are included in the omnibus (but not quite definitive) collection The Past Through Tomorrow: "Future History" Stories (Putnam: 1967, 667 pages) — unless otherwise indicated.

"Life-Line" (1939)

How much of the future do we really want to know? Oh, yeah? How much of your personal future? — Heinlein's first published story, an interesting meditation on mortality.

"And He Built a Crooked House" (1941)

A nice, custom house in Los Angeles — but also a tesseract with surprising dimensional properties. A neat multi-spatial tangle.

No tie-ins to other stories.

Reprinted in non-Future History collections and anthologies.

Not in The Past Through Tomorrow.

"Let There Be Light" (1940++)

Invention of the Douglas-Martin sun-power screens. — Enjoyable minor story, tweaked a couple if times for later collections.

Included in The Man Who Sold the Moon (six-story collection, 1950; many paperback printings have only four stories, including "Let There Be Light").

Not in The Past Through Tomorrow.

"The Roads Must Roll" (1940)

Novelet; the mechanized roads are a hybrid of railroad, freeway, and parallel conveyer belts. They dominate transportation for a while, with all that implies in terms of jobs, industry, and the economy. — Sometimes I think this could never happen; other times I read some bit in the news, and think that it may yet.

"Blowups Happen" (1940)

Novelet; about an atomic power plant, written before any existed. — The psychological-blowup half of the idea never rang quite true for me; yes, responsive people may need to work under enormous pressures, but they mostly continue to function. As a very young man in the U.S. Army I held for a while a small but extremely sensitive position which, for good reason, required a Top Secret clearance. Sure, psychological blowups can happen; but I see no inevitability.

The atomic-blowup half of the idea perhaps won't come true. But I certainly agree with Heinlein's idea that our future power generation and heavy industry belong in orbit, and even better, on Lunar Farside and elsewhere Out There. We have only one useful biosphere in the immediate vicinity, and we should be careful of it.

"The Man Who Sold the Moon" (1950)

A businessman decides to realize his dream of space travel by taking steps himself to make it a commercial possibility. — If in our real sub-lunar world, there is one man who arguably did more than any other to educate and persuade the American public about Luna and space travel, that man is Heinlein himself. Robert A. Heinlein truly may be called The Man Who Sold the Moon.

Short novel; first published in the collection The Man Who Sold the Moon. Chronological sequel is "Requiem", below.

"Delilah and the Space-Rigger" (1949)

The crew building the first space station.

"Space Jockey" (1947)

Slice-of-life: a space-pilot and his wife.

"Requiem" (1940)

A short but very moving follow-up to "The Man Who Sold the Moon", set years later.

"The Long Watch" (1948)

A young officer is standing watch in a nuclear-missile base on Luna, when a putsch begins. — As a teenager, years before I had anything to do with comparable responsibilities, this story struck me profoundly; later — and even now — it makes my scalp tingle. For some time it has been my conviction that most Medal of Honor decisions are made all alone, under the assumption that no one will ever know; and for most of them, no one ever does.

"Gentlemen, Be Seated" (1948)

A joke, but a bit of Lunar slice-of-life.

"The Black Pits of Luna" (1947)

Lost in the Lunar landscape.

"It's Great to be Back" (1946)

Nostalgia of the future.

"We Also Walk Dogs" (1941)

A future jack-of-all-trades service company.

"Searchlight" (1962)

How to find a blind girl lost somewhere on the vast desert area of the Moon? — A neat little problem.

"Ordeal in Space" (1947)

A space-pilot grounded for agoraphobia developed after drifting into emptiness in free fall. — Psychology and suspense work well together here.

"The Green Hills of Earth" (1947)

Rhysling, "the Blind Singer of the Spaceways". — The most famous Future History story.

"Logic of Empire" (1941)

Novelet; a smug citizen is shanghaied into indentured labor on an Old-Wet style Venus. — Interesting story on the idea that socioeconomic phases in the development of space travel inevitably will echo those of imperial expansion during earlier times on Earth.

"The Menace from Earth" (1957)

A teenage girl and her friends enjoy low-gravity flying, with wing harnesses, inside a two-mile-diameter air-filled Lunar cavern. — Matter-of-fact technology and charming slice-of-life romance at the same time. One of the last written, very smooth, one of the best of all the shorter Future History stories.

"If This Goes On —" (1940)

Short novel, about the revolt against a religious dictatorship in America. A young soldier goes from innocent and ignorant palace-guard of the Prophet, through disillusionment, induction into a Masonic underground lodge, to revolutionary officer. — I'd call this kind of story a "revolution procedural"; others by Heinlein (not in the Future History) are "Gulf" and The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress. Partly thanks to this warning story, the premise has lost much of its power to shock since it first appeared.

"Coventry" (1940)

Novelet; a citizen convicted of a crime chooses internal exile in the walled realm of Coventry rather than psychological rehabilitation. But Coventry isn't quite the free-wheeling individualist paradise he anticipated. — An adventure, but also a fascinating exploration of individuality versus conformity, voluntary and involuntary social behavior, and the origins of the State.

Misfit" (1939)

A young man joins a Civilian Conservation Corps for the Solar System. Introduces one of my favorite Heinlein characters, the modest mathematical genius Andrew Jackson "Slipstick" Libby.

Methuselah's Children (1941; 1958)

Novel, revised and expanded for book publication, 1958. A disturbing meditation on longevity, with the personal and political side-effects. Introduces the great Heinlein character Lazarus Long. One of Heinlein's important novels.

The Future History up to this point spans our next couple of centuries, starting more or less from now. There is a gap of more centuries before the subsequent stories, which are distant outliers beyond the main sequence.

"Universe" (1941)

The descendants of a starship crew on a multi-generational journey; they have lost all sense of journeying except in phrase and legend. Many are mutants. Their lives within the huge starship are savage, and they have had to re-invent primitive skills. — A memorable concept, exotic adventures inside the starship, with some really vivid scenes.

Novella; the first half of Orphans of the Sky.

Not in The Past Through Tomorrow.

"Common Sense" (1941)

Novella; close sequel to "Universe"; the second half of Orphans of the Sky.

Not in The Past Through Tomorrow.

Time Enough for Love (1973)

Substantial novel; Putnam, 1973. Further adventures and escapades of Lazarus Long, and friends and relations — given galactic elbow-room and sufficient longevity to mosey around and get involved in some of it. Read The Past Through Tomorrow first.

Not in The Past Through Tomorrow.

© 2001 Robert Wilfred Franson

I've been impelled to make a couple of tweaks to the above list after seeing James Gifford's scholarly discussion of the Future History stories and the Future History chart variants in his Robert A. Heinlein: A Reader's Companion. — RWF

RG advised on this.

magazine cover, bottom:

Astounding Science-Fiction

March 1941

by Hubert Rogers

| Troynovant, or Renewing Troy: | New | Contents | |||

| recurrent inspiration | Recent Updates | |||

|

www.Troynovant.com |

||||

|

Reviews |

||||

| Personae | Strata | Topography |

|

|||