Revolution in the Valley

The Insanely Great Story of

How the Mac Was Made

by Andy Hertzfeld

introduction by Steve Wozniak

contributions by Steve Capps, Donn Denman,

Bruce Horn, and Susan Kare

O'Reilly: Sebastopol, California: 2004

The insiders' view for the rest of us

Revolution in the Valley is an insiders' view of the creation of the epochal Apple Macintosh computer. Andy Hertzfeld was one of the central insiders; he began writing anecdotes for his Macintosh folklore collection which developed into this excellent and very readable history. There is some overlap and duplication as the focus shifts, but that's all right.

The book's subtitle is: The Insanely Great Story of How the Mac Was Made. Insanely great is Steve Jobs' visionary target for what Apple Computer's Macintosh development team should be striving for: not a good product, not even a great one, but something insanely great that would change the world.

And it was insanely great, and it changed the world.

Revolution in the Valley has the flavor of a memoir and photo album. Yet there's a lot of more-or-less technical stuff here. Perhaps the most appropriate readers outside those involved at Apple Computer would be: curious or reminiscent owners of Macintoshes, especially early models; historically-minded programmers; anyone interested in human usability design, particularly the graphical user interface; students of the history of technology; or students of the psychology of how teams and enterprises function. — I happen to be somewhat representative of all these groups, so I may be one of the more ideally targeted readers. But if you fit into any of the groups, you should find plenty to enjoy in the book.

This is very much a history of people, with lots of portraits of bright folks dealing with interesting challenges: Steve Jobs of course; Bill Atkinson, Steven Capps, Donn Denman, Joanna Hoffman, Bruce Horn, Susan Kare, Larry Kenyon, Jef Raskin, Burrell Smith, Randy Wigginton, and a few others. And some who were perhaps more stumbling blocks than visionary builders.

![]() The book is stuffed with fun details. For instance, Andy Hertzfeld himself wrote Puzzle, the tiny Desk Accessory program that emulates the 4x4 plastic puzzle with fifteen numbers in squares and one empty square; mousing replaces the fingertips. I was a very quick operator of such a plastic puzzle as a kid (I still have it). Hertzfeld also wrote the routine that displayed "the very first image on the very first Macintosh": a scanned rendering of one of my own all-time favorite characters, Carl Barks' Scrooge McDuck.

The book is stuffed with fun details. For instance, Andy Hertzfeld himself wrote Puzzle, the tiny Desk Accessory program that emulates the 4x4 plastic puzzle with fifteen numbers in squares and one empty square; mousing replaces the fingertips. I was a very quick operator of such a plastic puzzle as a kid (I still have it). Hertzfeld also wrote the routine that displayed "the very first image on the very first Macintosh": a scanned rendering of one of my own all-time favorite characters, Carl Barks' Scrooge McDuck.

There's a nice discussion of the famous Macintosh 1984 television commercial.

Some managerial walking-dead ideas keep rising from the grave, however often they're staked. I've run into this foolishness myself more than once:

The first computer I ever likedIn early 1982, the Lisa software team was trying to buckle down for the big push to ship the software within the next six months. Some of the managers decided it would be a good idea to track the progress of each individual engineer in terms of the amount of code they wrote from week to week. They devised a form that each engineer was required to submit every Friday, which included a field for the number of lines of code written that week.

Bill Atkinson, the author of QuickDraw and the main user interface designer, who was by far the most important Lisa implementer, thought lines of code was a silly measure of software productivity. He thought his goal was to write as small and fast a program as possible, and the lines of code metric only encouraged writing sloppy, bloated, broken code.

He had recently worked on optimizing QuickDraw's region calculation machinery, and had completely rewritten the region engine using a simpler, more general algorithm — which, after some tweaking, made region operations almost six times faster. As a byproduct, the rewrite also saved around 2,000 lines of code.

He was just putting the finishing touches on the optimization when it was time to fill out the management form for the first time. When he got to the lines of code part, he thought about it for a second, and then wrote in the number: -2,000.

I'm not sure how the managers reacted, but I do know that after a couple more weeks they stopped asking Bill to fill out the form, and he gladly complied.

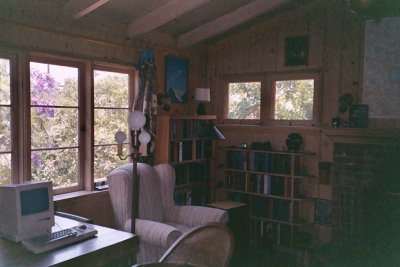

My own first Macintosh, bought in May 1984, had the standard 9"-diagonal black-and-white screen, 128k of RAM, and a single 400k floppy drive. It came with System 1.1f, almost immediately upgraded to run System 1.1g. There was virtually no software available beyond the Apple-furnished MacWrite and MacPaint. Hertzfeld discusses a raft of distinctive hardware and software characteristics of the Macintosh, how they were developed, and why the designers made the choices they did.

One early program that I do not see mentioned is ResEdit, Apple's resource editor. After I'd had my Mac a while, I began ordering ResEdit and other Mac goodies from the Berkeley Macintosh User Group. ResEdit allowed one to alter icons, fonts, and menus, and tweak other operating system internals. Meddling with the live System running your computer was strongly discouraged, and this was graphically emphasized in ResEdit's own icon, which was a jack-in-the-box with crosses for eyes — indicating a dead System was the likely result of using it. This was appropriate. Doing assorted ad hoc customizations over the next few years, I crashed the Mac System plenty of times. Fun, though.

There are lots of illustrations in Revolution in the Valley: people, sketches, designs, screen shots, prototypes, publicity. Some of the illustrations allow me to re-breathe the freshness of those times. Lots of little icons, now old-fashioned and obsolete. The cover of the first issue of Macworld magazine, which I bought in a store; I sent in to start my subscription with the second issue. Many, many more.

Revolution in the Valley is a unique history, and very much a book to enjoy.

© 2008 Robert Wilfred Franson

Steven Levy's

Insanely Great

The Life and Times of Macintosh,

the Computer That Changed Everything<

ComWeb at Troynovant

mail & communications,

codes & ciphers, computing,

networks, robots, the Web

| Troynovant, or Renewing Troy: | New | Contents | |||

| recurrent inspiration | Recent Updates | |||

|

www.Troynovant.com |

||||

|

Reviews |

||||

| Personae | Strata | Topography |

|

|||