First Contacts:

The Essential Murray Leinster

by Murray Leinster

NESFA Press

New England Science Fiction Association

Framingham, Massachusetts; 1998

464 pages

A fraction of the essential

I'm not sure there can be any such thing as the essential Murray Leinster — the man wrote far too much science fiction for that, entertaining readers across half a century of writing beginning in 1919, and occasionally sparking ideas that broadened into new realms of speculation, widening the way we think about time or interstellar travel. Leinster wrote many stories for the slick-paper magazines such as The Saturday Evening Post, generally under his real name, Will F. Jenkins. First Contacts: The Essential Murray Leinster includes two dozen stories from 1934-1964: half from Astounding Science Fiction, two previously unpublished, two from the slick magazines, and the rest from other science fiction magazines.

First Contacts takes its title from Leinster's famous 1945 novelet "First Contact", on the initial encounter between humans and an alien race, and more or less gathers stories on this theme. Many consider "First Contact" to be the story that defined "first contact" as a problem in the sense of a chess problem with a mostly-empty board and just a few pieces in tense juxtaposition. In this story, the situation is symmetric: a Terrestrial starship on a scientific exploration to the Crab Nebula meets an alien starship on a similar mission, with an equivalent level of technology. Should they fight, perhaps to mutual destruction? Or flee, risking that the other ship will follow them home, learning their location without giving away their own? But the aliens are thinking along the same lines. It is a mutual problem with checkmate in two moves. Or —?

A knotty situation, based on the underlying reality of cultures encountering others throughout our history. The problem of "First Contact" is whether a way can be found to break the deadly-embrace of the zero-sum trap in which the two starships face each other. — But as a story, it is nebulously sparse in plot and characters. As a chess-like problem, it has way too many things wrong with it. Since I first read the story as a teenager, I've never been able to consider this stand-off situation as plausible, nor the solution in "First Contact" as anything which either humans or aliens would agree to unless intoxicated by fermented Crab Nebula space-dust.

The rest of the First Contacts collection is livelier, ranging from good to excellent. "Proxima Centauri" appeared in 1935, antedating "First Contact" with almost the same theme; although it has a primitive story-line it is a better story and a more realpolitik situation. (Unfortunately its title is misspelled in its top-of-page titles throughout the story; eighteen misspellings — if not a record, surely a contender.)

"If You Was a Moklin" from 1957 describes meeting an alien race that admires us too much; this manages to be matter-of-fact, funny, and disquieting. The more you think about it, the more disquieting.

Three stories all printed in Astounding Science Fiction in 1945 (the same year as "First Contact") show quite a range. "The Power" is a lovely tale in the form of several recently discovered Renaissance letters. It deals with a favorite concept of editor John W. Campbell's, that science sufficiently more advanced than one's own appears to be magic. "Pipeline to Pluto" is a tough, grim story of tough, grim criminals. Balancing that is "The Ethical Equations", a sly, semi-serious exploration of patterns of human conduct:

Scary with army antsThe Ethical Equations, of course, link conduct with probability, and give mathematical proof that certain patterns of conduct increase the probability of certain kinds of coincidences, But nobody ever expected them to have any really practical effect. Elucidation of the laws of chance did not stop gambling, though it did make life insurance practical. The Ethical Equations weren't expected to be even as useful as that. ...

"Doomsday Deferred" (1949, as by Will F. Jenkins) concerns army ants in the jungle, a scary re-thinking of H. G. Wells' "The Empire of the Ants" (1905). Leinster's version is more deeply frightening.

Milhao is in Brazil, but from it the Andes can be seen against the sky at sunset. It is a town the jungle unfortunately did not finish burying when the rubber boom collapsed. ...

I got there after a river steamer refused to go any farther, and after four days more in a canoe with paddlers who had lived on or near river water all their lives without once taking a bath in it. When I got to Milhao, I wished myself back in the canoe. It's that sort of place.

... Yet even Milhao is better than farther upstream. You don't want to meet these army ants.

Murray Leinster's foresight or timeless topicality, has not flagged. First Contacts leads off with the seminal personal-computer story, "A Logic Named Joe". At its other end the collection wraps up with the previously unpublished "The Great Catastrophe" about intercontinental aerial warfare, written in 1919 but sold to a failing magazine; and "To All Fat Policemen" from 1946, not science fiction but a neat little parable about America. Editor Joe Rico nicely introduces these last two.

Several stories deal with bacteriological warfare or criminality. "Symbiosis" (1947) appeared in a slick magazine with a readership of millions. "Cure for a Ylith" is an anti-dictatorship story from 1949. The novelet "Plague on Kryder II" (1964) is part of Leinster's Med Ship series.

"Sidewise in Time" appeared in Astounding Stories (not yet the Campbell-edited Astounding Science Fiction) in 1934, and is one of the true essentials in this collection. "Sidewise in Time" is a pioneering study in alternate histories, but not world-lines side-by-side as developed thoroughly in the later vision of H. Beam Piper's Paratime. Here we stumble through historical chaos, spacetime become unstable with chunks of time shuffled and juxtaposed in earthquake-like timeslips. A great adventure.

"The Fourth-Dimensional Demonstrator" (Astounding Stories, 1935) is a hilarious little classic on the nexus where time-travel turns into duplication. Years later Leinster still is having fun with time. In "Sam, This Is You" (Galaxy, 1955), a telephone lineman gets an unexpected call:

The right prize but the wrong story"This is you," the voice on the wire repeated. "You, Sam Yoder. Don't you recognize your own voice? This is you, Sam Yoder, calling from the twelfth of July. Don't hang up!"

On the other hand, "Exploration Team" presumably is included in First Contacts because it won a Hugo Award for best science fiction novelet of 1956. It's one of Leinster's four Colonial Survey stories, and despite Kodiak bears as explorer's helpers, the least interesting. Unfortunately when this series was collected into book form for Gnome Press, someone decided that it would look more like a novel if the four Colonial Survey officers in the four stories were conflated into one person and given the same name: Bordman of "Sand Doom". This doesn't work because Roane of "Exploration Team" is a tag-along having little in common with the others, especially the competent Hardwick who solves the exotic problem of "The Swamp Was Upside Down" (not included here). First Contacts picks up the unfortunate revision of "Exploration Team". (Isaac Asimov's anthology The Hugo Winners reprints the better original from Astounding.)

On First Contacts' page 395 is a misattributed passage of dialogue from the Gnome Press version of "Exploration Team", confusing the characterization further; it should read: "Dammit," snapped Huyghens, "if so I'll go see. ..." — The illegal explorer Huyghens, not the Colonial Survey officer, is the active character in "Exploration Team". The Roman numerals indicating story sections are missing, demoting sectional divisions in the narrative to unexplained lurches.

The Essential Murray Leinster? Certainly these are fine and characteristic, but plenty of other essentials are not included in NESFA's First Contacts. Murray Leinster also wrote a perfect space-pirate novel, The Pirates of Ersatz (1959; paperback as The Pirates of Zan), where the humor and economics of interstellar trade intersect. He wrote some enjoyably odd fantasy adventures as well as lots of other memorable science fiction. First Contacts is a good collection, with some stories outstanding and all entertaining, but only a sampler of Murray Leinster's work.

"Nobody Saw the Ship" is a suspenseful story of a shepherd and his dog facing alien danger. Some of the less-essential included here also are enjoyable and thought-provoking:

"De Profundis" (1945) is slight but with a neat sub-aquatic setting, and was a favorite of Leinster's. In an article he once wrote for me, Leinster says of this story:

I like it because everybody's heard of men seeing sea-serpents and telling other men, who didn't believe them. "De Profundis" is a story about a sea-serpent seeing a man. And he told other sea-serpents. And they didn't believe him.

Murray Leinster

"Reverie"

Science Fiction Review (Franson/Sandin)

Number 18, 27 April 1964

Another little inversion-of-viewpoint tale is "Keyhole" (1951), a Lunar first-contact story. In the article "Reverie", Leinster went on to say that he most enjoyed remembering "Keyhole" of all his science fiction:

I had a ten-year-old daughter when I wrote that story. She read it and zestfully told me a story about a man who wanted to study the reactions of a chimpanzee. He led the chimp into a room full of things a chimp should find interesting. He went out and closed the door, and then put his eye to the keyhole to see what the chimp was doing. He found himself looking into an interested brown eye only inches from his own. The chimp was looking through the keyhole, too, to see what the man was about.

I put my daughter's tale as a preface and a coda to my own yarn and called it "Keyhole."

Murray Leinster likes to remind us that when we look out at that vast universe, someone out there may be looking at us with their very own viewpoint. And when we reach out to explore, others may be exploring right back at us. Be wary, and keep your sense of humor.

© 2001 Robert Wilfred Franson

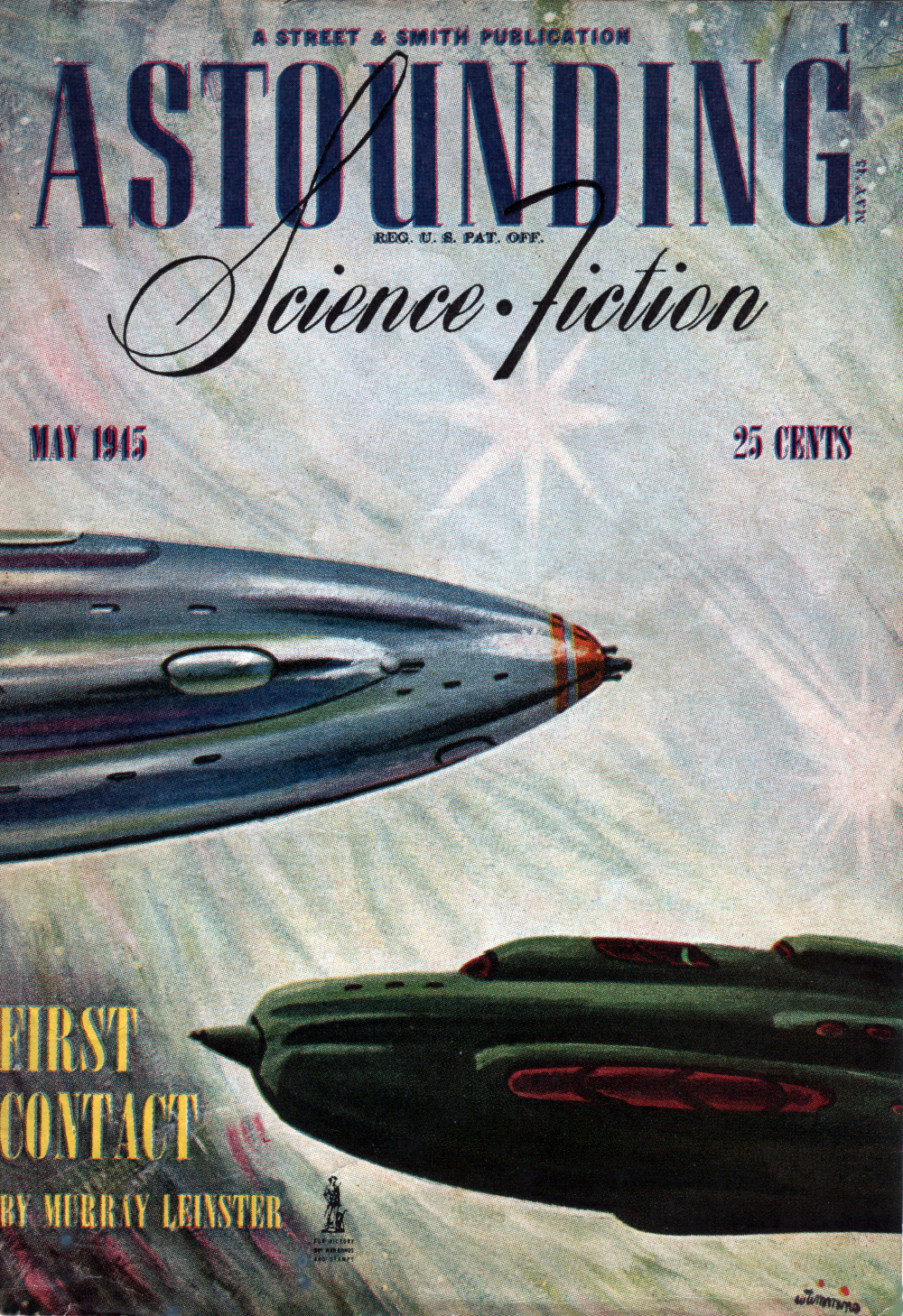

magazine cover, bottom:

Astounding May 1945

by William Timmins

The Jenkins family's official site for

Murray Leinster / Will F. Jenkins

| Troynovant, or Renewing Troy: | New | Contents | |||

| recurrent inspiration | Recent Updates | |||

|

www.Troynovant.com |

||||

|

Reviews |

||||

| Personae | Strata | Topography |

|

|||