The Selected Short Stories

of Eric Frank Russell

edited by Rick Katze

NESFA Press

New England Science Fiction Association

Framingham, Massachusetts: 2000

701 pages

The Russell tone in a fine & solid collection

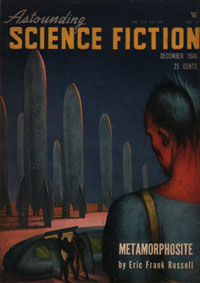

Major Ingredients: The Selected Short Stories of Eric Frank Russell (the title page omits the word Short) is a solid collection, and a fine one. Rick Katze, the editor, even in this big space of 700 pages could fit only thirty stories, and he regrets excluding other good stories. Most of these first appeared in Astounding Science Fiction magazine in the 1940s and 1950s; it's a nice editorial practice to give the original magazine dates both on the acknowledgments page and on each story's title page.

Major Ingredients: The Selected Short Stories of Eric Frank Russell (the title page omits the word Short) is a solid collection, and a fine one. Rick Katze, the editor, even in this big space of 700 pages could fit only thirty stories, and he regrets excluding other good stories. Most of these first appeared in Astounding Science Fiction magazine in the 1940s and 1950s; it's a nice editorial practice to give the original magazine dates both on the acknowledgments page and on each story's title page.

Eric Frank Russell (1905-1978) always has been one of my very favorite science fiction writers, one who helped set the tone for the best science fiction to a standard to which few writers attain. His stories tend to be relaxed, humorous, with likely people in believable situations. Russell has a strong anti-authoritarian streak, which often puts his heroes at odds with their own government, space navy, and so on, while also dealing with more overt foes.

Russell's tone covers a lot of territory in a small space. These are the openings of two stories, both set on Earth.

From "Basic Right":

They came out of the starfield under the Earth, from the region of a brilliant sun called Sigma Octantis. Ten huge copper-colored ships. Nobody saw them land. They were astute enough to sit a while in the howling wastes of Antarctica, scout around and seize all twenty members of the International South Polar Expedition.

From "Fast Falls the Eventide":

Building blocksIt was an old world, incredibly old, with a pitted moon and a dying sun and a sky too thin to hold a summer cloud. There were trees upon it but not the trees of yore, for these were the result of aeons of gradual accommodation. They inhaled and exhaled far less than did their distant forebears and they sucked more persistently at the aged soil.

Three other stories included here that first appeared as individual pieces in Astounding Science Fiction later became parts of excellent novels:

"Jay Score" (May 1941) is the opening novelet of the closely related four that make up Men, Martians and Machines. Simpler with less fun than the later Jay Score stories, but it introduces the memorable title character and the rest of a crew of space explorers.

"And Then There Were None" (May 1951) later was employed as the long climactic episode of a classic libertarian novel, The Great Explosion (1962) — but is quite enjoyable independently, and reading the story won't spoil the novel. The contrast is striking and hilarious between military regimentation in a great ship from Earth, versus a free society based on values and obligations voluntarily assumed. The novella portrays what surely must be one of the most relaxed utopias ever.

"Plus X" (June 1956) is a novella on one of Russell's favorite themes, the escape of a prisoner of war or group of them, more by native wit and imagination than technical skills. Bibliographically, this story is unusual in existing in three different lengths: as The Space Willies, a novel in the Ace Double paperback line (1958), and in its full length as Next of Kin (Dobson, 1959). I'd advise reading the great Next of Kin instead of the shorter versions.

The collected or expanded works deserve permanent availability in print. Together these stories make up about a hundred pages, or a seventh of the collection, squeezing out lesser but memorable stories. The NESFA Press collection of five of Russell's novels, Entities, includes the complete novel Next of Kin.

Incidentally, NESFA Press is to be commended for including sources for the stories — but don't take it for gospel if you're writing a thesis on Russell. For instance, the acknowledgment for "The Army Comes to Venus" notes its American publication in Fantastic Universe, May 1959; but that story's first appearance, titled "Sustained Pressure", is in the British Nebula Science Fiction, December 1953.

Another fine story of a solitary prisoner of aliens is "Now Inhale" (linked titles are reviewed at Troynovant). In "Nuisance Value" we have a prisoner of war camp on an alien planet; in "Basic Right" the entire Earth is captured — for a while.

These escape stories are entertainment: humorous and psychologically pointed. They are not Escape from Sobibor (a Nazi death camp near Lublin) stories, although if Russell had written such a World War II underground or escape story it might have been a best-seller.

An afterword to Major Ingredients by Mike Resnick briefly analyzes why Russell does not have the fame and in-print status he deserves — "He should have been a contender" — and lays out some largely cogent principles. I've wondered about Russell not being often enough in-print, and Resnick sounds reasonable. But while other authors flare and die — many are dead on the page even while staying in print and clogging the bookshelves — I've always considered that Russell's place is among the first rank of science fiction.

Jack L. Chalker's introduction also emphasizes how many of Russell's heroes are social misfits. These heroes are often pilots or space scouts, chafing under ponderous authority but able to shine when operating out on the frontier, living by their wits.

A wonderfully pointed application of C. Northcote Parkinson's classic Parkinson's Law is "Study in Still Life", a fictional but all-too-true observation of how to succeed even though trapped in bureaucracy. Here the hero is a disabled space pilot, stuck in a desk job. But Russell has "the gift of laughter and a sense that the world was mad" that Kafka does not; Russell's hero retains the wit, humor, and patience to master even this modern morass. — In "Allamagoosa", a space-navy crew tries to slide around a bureaucratic trifle; here we bystanders may nod wisely and contain the chuckles while we tiptoe away. "Top Secret" is another favorite of mine, a hilarious example of cryptology in action.

"Metamorphosite", "Fast Falls the Eventide", and "Dear Devil" are more serious stories, giving greatly differing futures for humanity; Russell has a wide conception of what human-kind is capable, or what humanity really means. — But "Homo Saps" and "Into Your Tent I'll Creep" suggest that maybe we aren't the top dogs even in our own neighborhood. — And the gemlike "Hobbyist" suggests a different kind of human beginnings.

Russell wrote both patriotic and anti-war stories. A simple but moving example of space-naval officers' education is "Minor Ingredient". Alongside this theme, Major Ingredients includes the powerful little anti-war story "I Am Nothing", which itself is counterpointed by the global warning of "Last Blast". The emotional range, the psychological puzzles, run from homesickness in "Tieline" to logic in "Diabologic" to the fascinating study of the pace of life in "The Waitabits".

Courage, patience; humor, wit, and imagination — all major ingredients, at a desk or between the stars.

© 2001 Robert Wilfred Franson

Astounding December 1946 cover

by Alejandro Canedo;

| Troynovant, or Renewing Troy: | New | Contents | |||

| recurrent inspiration | Recent Updates | |||

|

www.Troynovant.com |

||||

|

Reviews |

||||

| Personae | Strata | Topography |

|

|||