Sinister Barrier

by Eric Frank Russell

Unknown, March 1939

revised & expanded —

Fantasy Press: Reading, Pennsylvania; 1948

253 pages

collected (minus Russell's Foreword) in —

May 2002

The fence and the warnings

"Swift death awaits the first cow that leads a revolt against milking," mused Professor Peder Bjornsen. It was a new slant, and a wicked one. He passed long, slender fingers through prematurely white hair. His eyes, strangely protruding, filled with uncanny light, stared out of his office window which gaped on the third level above traffic swirling through Stockholm's busy Hötorget. But those eyes were not looking at the traffic.

Sinister Barrier is Eric Frank Russell's first novel. It was quite a debut. The original version was chosen by editor John W. Campbell to lead off the March 1939 first issue of his legendary fantasy magazine Unknown, companion to Astounding Science Fiction. The novel is solid science fiction, with subtleties and even profundities that may not be obvious in the thrilling pace of the plot.

Minutes after Professor Bjornsen's thought (above) that opens Sinister Barrier, the scientist is dead — apparently of heart failure. Other scientists in Europe and America with whom he has been in communication attempt to reproduce his experimental results, to see whatever Bjornsen saw.

A couple of weeks later, Doctor Hans Luther agitatedly calls the editor of the Dortmund Zeitung, begins to explain with great urgency,

"Earth is belted with a warning streamer that says: KEEP OFF THE GRASS!" Luther watched the stairs and sweated.

"Ha-ha!" responded Vogel, without mirth. His heavy face moved in the tiny vision-screen above the telephone, bore the patient expression of one accustomed to the eccentricities of scientists.

"Listen!" yelled Luther. He wiped his forehead with the back of a quivering hand. "You know me. You know that I do not tell lies, I do not joke. I tell you nothing which I cannot prove. So I tell you that now and perhaps for thousands of years past, this troubled world of ours ... a-ah! ... a-a-ah!"

Luther dies, perhaps of heart failure, and whatever he was intent on revealing is not completed.

Bill Graham is "a government liaison officer between scientists and the U.S. Department of Special Finance". When he sees a man he knows, phlegmatic Professor Walter Mayo, plunge to his death from a New York skyscraper for no obvious reason, Graham begins to get caught up in the mystery of the scientists' deaths. There's a parallel case the same day, another scientist —

"The medical examiner maintains that he died of heart disease — yet he expired while shooting at nothing."

Investigating this case, Graham meets police lieutenant Art Wohl. Together, Graham and Wohl try to track down why the scientists have died — what were they doing, what did they have in common? What information were they exchanging? What risky technique or dangerous insight had they learned directly or indirectly from Professor Bjornsen? One of the clues seems to be that some of the late scientists were experimenting with iodine, a substance found richly in seafood. Graham remembers obscure notes left by one of the scientists:

Sailors are notoriously susceptible.

Susceptible to what? [Graham wonders.] To illusions and to maritime superstitions based upon illusions? — the sea serpent, the sirens, the Flying Dutchman, mermaids, and the bleached, bloated, soul-clutching things whose clammy faces bob and wail in the moonlit wake?

Must extend the notion, and get data showing how seaboard dwellers compare with country folk.

(The scientist's notes are offset with italics, as above; the fine NESFA collection Entities unfortunately loses Russell's italicization.)

Graham is an excellent Russellian investigator: intelligent, brave, and flexible. Iodine, mescal, methylene blue? Scientists and doctors specializing in optics who drop dead in unusual circumstances? Each matter-of-fact step in the investigation complicates the mystery, exacerbate the weirdness — until Graham and Wohl realize that they may be getting to know too much themselves. Sinister Barrier is a great scientific adventure in the true Baconian sense, fast-paced and thrilling.

Later in the novel another courageous scientist, Professor Beach, points out to Graham that —

"When Galileo peered incredulously through his telescope he found data that had stood before millions of uncomprehending eyes for countless centuries ..."

And —

"... the microscope ... disclosed a fact that had been right under the world's nose since the dawn of time, yet never had been suspected — the fact that we share our world, our whole existence, with a veritable multitude of living creatures hidden beyond the limits of our natural sight, hidden in the infinitely small. Think of it ... living, active animals swarming around us, above us, below us, within us, fighting, breeding and dying even within our own blood-streams, yet remaining completely concealed, unguessed-at, until the microscope lent power to our inadequate eyes."

So in the most straightforward sense it is a question of vision; and as so often, of the courage and persuasiveness of pioneer visionaries.

Russell opens his Foreword to the 1948 edition with an odd and arresting statement:

It would be idle to pretend and dishonest to suggest that Sinister Barrier is anything other than fiction. Some may regard it as fantasy because it is placed in the future and depicts certain developments likely in times to come. But I regard it as a sort of fact-fiction solely because I do sincerely believe that if ever a story was based upon facts it is this one.

Sinister Barrier is as true a story as it is possible to concoct while presenting believe-it-or-not truths in the guise of entertainment. It derives its fantastic atmosphere only from the queerness, the eccentricity, the complete inexplicability — so far as dogmatic science is concerned — of the established facts which gave it birth. These facts are myriad. I have them in the form of a thousand press clippings ...

In his Foreword, Russell credits three men with the "cumulative effect" that led to the story jelling for him. One asked, "Since everyone wants peace, why don't we get it?" The second, "If there are extra-terrestrial races further advanced than ourselves, why haven't they visited us already?"

Until I encountered the third, Charles Fort, it didn't occur to me that perhaps we had been visited and were still being visited, without being aware of it. Charles Fort gave me what might well be the answer to both these questions. Casually but devastatingly, he said, "I think we're property." And that is the plot of Sinister Barrier.

And so the title. Earth is effectively fenced, its self-proclaimed human masters are in fact themselves herded property of things unseen — at least, unseen by "normal people" in "normal circumstances". And what happens if a few people begin to see, and try to spread the news? Swift death awaits the first cow that leads a revolt against milking.

Charles Fort (1874-1932) was the premier collector of documented oddities and reports of unexplained events. In the course of the novel Russell provides a small clutch of relevant and fascinating Fortean examples. Graham and others speculate a little about extra-sensory perception in general, what editor John W. Campbell later would call psionics. Russell also finds opportunity to mention mysterious appearances — Kaspar Hauser; and disappearances — Benjamin Bathurst. Russell was long involved in Fortean Society affairs.

Along with Fortean acknowledgments in his Foreword, Russell thanks:

John W. Campbell, Jr., editor of Astounding Science-Fiction and Unknown Worlds, for kicking me around until this story bore more resemblance to a story.

And for the New York newspaper clipping — eight starlings falling from the sky in a group, dead without visible injury — that sets the initial tone for the novel:

Julius Schwartz, editor of Superman, for providing the press clipping shown on a following page, and with it the spark-plug which got me going.

And, flatteringly but sincerely:

Whose is the barrier?To thousands of science-fiction fans for being willing to enter the gates of hell — providing that they get in on the ground floor — and thus being willing to read this yarn.

Do we want to see, do we want to know, even if seeing the truth and knowing what it means changes our comfortable context and puts us into a kind of hell, or seems to? Toward the middle of Sinister Barrier, the title phrase occurs in an almost throwaway sense, as Professor Beach tells Graham:

"The scale of electro-magnetic vibrations extends over sixty octaves, of which the human eye can see but one. Beyond that sinister barrier of our limitations, outside that poor, ineffective range of vision, bossing every man-jack of us from the cradle to the grave, invisibly preying on us as ruthlessly as any parasite, are our malicious, all-powerful lords and masters — the creatures who really own the Earth!"

But this is another kind of barrier.

If the doors of perception were cleansed every thing would appear to man as it is: infinite.William Blake

The Marriage of Heaven and Hell

© 2002 Robert Wilfred Franson

Breathers at Troynovant

lifeforms & biologic processes:

wildlife & pets, evolution & ecology,

health, medicine, & disease

Mentality at Troynovant

the mind and mental operation

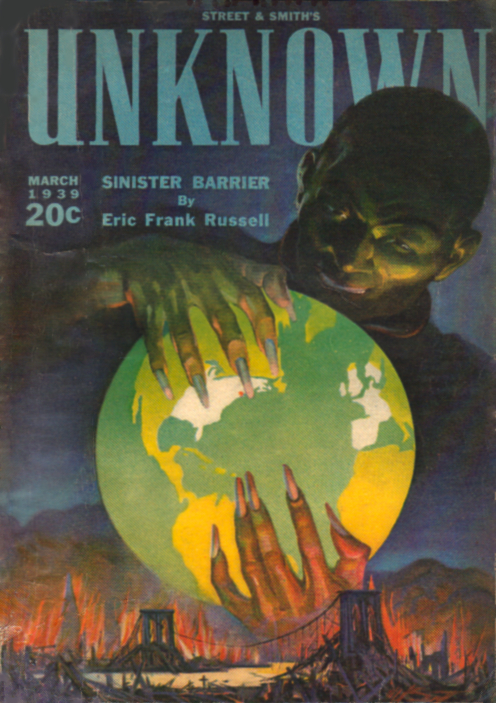

magazine cover, bottom:

Unknown

March 1939

by H. W. Scott

[a symbolic but monstrously vivid treatment;

do notice the direction of his gaze]

ReFuture at Troynovant

history of science fiction

& progress of fantasy

| Troynovant, or Renewing Troy: | New | Contents | |||

| recurrent inspiration | Recent Updates | |||

|

www.Troynovant.com |

||||

|

Reviews |

||||

| Personae | Strata | Topography |

|

|||