Porterhouse Blue

by Tom Sharpe

Secker & Warburg: London, 1974

A hearty feast for scholars

English novels set at either of the two centuries-old universities, Cambridge or Oxford, cannot be too coy or generic about the locale. These two with their component Colleges are well-known in Britain and much more familiar abroad than are American schools. In the English university grand tradition, a novel's setting must be Cambridge or Oxford or an imaginary, and sometimes apologized-for, fusion referred to as Oxbridge. Dorothy Sayers' Gaudy Night and Michael Innes' Seven Suspects are other English university mystery-novels.

In Porterhouse Blue, Tom Sharpe postulates an additional College at Cambridge, slumbering within five centuries of walled traditions and calmly enamored of them, named Porterhouse. In language which Porterhouse dons and graduates would appreciate — if other Oxbridge colleges are fine old wine, and American schools are new flat beer, then Porterhouse is the best, true, and ancient brandy. "A sturdy self-reliance except in scholarship is the mark of the Porterhouse man." There is an earthy directness about Porterhouse typified by its love for well-spread tables.

Given that food in fine quality and in great quantities is the centuries-old Porterhouse hallmark, Sharpe appropriately opens with an account of the beloved annual College Feast, the first one attended by the new Master of Porterhouse, the forcibly-retired politician Sir Godber Evans:

The receding tide of traditionIt was a fine Feast. No one, not even the Praelector who was so old he could remember the Feast of '09, could recall its equal — and Porterhouse is famous for its food. There was Caviar and Soupe a l'Oignon, Turbot au Champagne, Swan stuffed with Widgeon, and finally, in memory of the Founder, Beefsteak from an ox roasted whole in the great fireplace of the College Hall. Each course had a different wine and each place was laid with five glasses. ...

For two hours the members of Porterhouse were lost to the world, immersed in an ancient ritual that spanned the centuries. ...

Only the new Master differed from his predecessors. Seated at the High Table, Sir Godber Evans picked at his swan with a delicate hesitancy that was in marked contrast to the frank enjoyment of the Fellows.

As the swan song of his reformist career, the new Master of the college is determined to change Porterhouse, and change it for the better, in the cause of social progress.

Determinedly opposed to modernizing are Skullion, the stolid and entrenched Head Porter at Porterhouse; as well as higher educators such as the Dean, Senior Tutor, Praelector, Bursar, and the Chaplain. It's a great bricks-and-mortarboard, town-and-gown conflict in the old college.

Tom Sharpe's sense of Englishness and of satire always are wonderfully thick on the ground. Here is an outstanding passage where neat satire is accompanied by one of his rarer poetic fancies. What to do about the assault of modern education being brought into the College by Sir Godber Evans? The Dean of Porterhouse goes out to seek advice and assistance from a well-placed former student at Porterhouse, now a retired General, Sir Cathcart:

Elevating wit, delightful characters'Trouble with this Godber Evans fellow is he comes from poor stock,' continued Sir Cathcart when he had filled their glasses. 'Doesn't understand men. Hasn't got generations of county stock behind him. No leadership qualities. Got to have lived with animals to understand men, working men. ... No use filling their heads with a whole lot of ideas they can't use. Bloody nonsense, half this education lark.'

'I quite agree,' said the Dean. 'Educating people above their station has been one of the great mistakes of this century. What this country requires is an educated elite. What it's had in fact, for the past three hundred years.' ...

The Dean's head nodded on his chest. The fire, the brandy and the ubiquitous central heating in Coft Castle mingled with the warmth of Sir Cathcart's sentiments to take their toll of his concentration. He was dimly aware of the rumble of the General's imprecations, distant and receding like some tide going out across the mudflats of an estuary where once the fleet had lain at anchor. All empty now, the ships gone, dismantled, scrapped, the evidence of might deplenished, only a sandpiper with Sir Godber's face poking its beak into the sludge. The Dean was asleep.

The entire novel is rich with humor, wit, puns; not sprinkled onto the story but woven into the plot like jewels in brocade. Re-readings show up double meanings missed earlier, in names, situations, off-hand comments. The title Porterhouse Blue is itself a portmanteu phrase in Fowler's sense, packing an amazing number of references into two words.

There is a fine sequel, Grantchester Grind; although Porterhouse Blue is complete in itself.

Porterhouse Blue and Grantchester Grind contain much less violence and overt bawdiness than Tom Sharpe's first two novels, the riotously indecent South Africa satires Riotous Assembly and Indecent Exposure. Yet neither are these for children, for the tender-minded, nor for anyone austerely righteous or politically correct, untempered by humor. There are literate bawdy jokes and puns of the kind that lace some of Shakespeare's plays, and downright sex-farce worthy of Aristophanes and the phallic Old Comedy of the Greeks. Outrages of modesty or decorum are common. The plot races along, touched-up by new collegiate raciness to brighten or frighten the old walls of Porterhouse.

Ah, education! Has the Fleet's high tide gone out forever, and only the officious sludge on the shore left to future generations? I find Porterhouse Blue very, very funny; it is exemplary at once of useful satire, witty tale-telling, and hilarious entertainment.

Adults Only.

© 2004 Robert Wilfred Franson

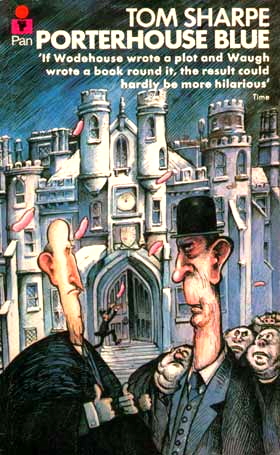

paperback cover, above left:

Porterhouse Blue

by Paul Sample

R. W. Franson's review of

Grantchester Grind

by Tom Sharpe

Schooling at Troynovant

school, college, ongoing learning

| Troynovant, or Renewing Troy: | New | Contents | |||

| recurrent inspiration | Recent Updates | |||

|

www.Troynovant.com |

||||

|

Reviews |

||||

| Personae | Strata | Topography |

|

|||