Penrod: His Complete Story

by Booth Tarkington

Penrod, 1914

Penrod and Sam, 1916

Penrod Jashber, 1929

illustrated by Gordon Grant:

4 color pages; 12 b&w pages; 69 b&w chapter headings.

Doubleday: New York, 1931

590 pages

The friendly neighborhood, circa 1913

"Oh, Penrod!" Miss Lowe exclaimed. "Good gracious!"

"I don't see why he came. He declines to dance — rudely, too!"

"I don't think the little girls will mind that so much!" Miss Lowe said. "If you'd come to the dancing class some Friday with Amy and me, you'd understand why."

They moved away. Penrod heard his name again mentioned between them as they went, and, though he did not catch the accompanying remark, he was inclined to think it unfavourable. He remained where he was, brooding morbidly.

He understood that the government was against him, nor was his judgment at fault in this conclusion.

Booth Tarkington provides an engaging introduction to Penrod: His Complete Story, written in the 'Teens of the Twentieth Century:

This book owes its existence to a lady connected by marriage with the writer, for at the time of her consent to become thus related she made virtually the condition that he should write something about a boy. ...

... the compilation has been made and is here displayed as the author's final word upon "a boy's doings in the days when the stable was empty but not yet rebuilt into a garage."

So we may take it that Penrod Schofield is eleven years old in 1913. His friends Sam Williams and Maurice Levy and others are about the same age, as is Georgie Bassett, "the best boy in town" according to the adults — Penrod is generally rated the worst, not for really bad activities but for the unfortunate or under-appreciated results of sheer boyish high energy and inventiveness.

The novel is funny. It is strewn with episodes that I hope will make you smile, and punctuated with youthful hijinks and predicaments that may well make you laugh out loud. It did for me when I first read it at about Penrod's age, and still does.

The novel is funny. It is strewn with episodes that I hope will make you smile, and punctuated with youthful hijinks and predicaments that may well make you laugh out loud. It did for me when I first read it at about Penrod's age, and still does.

The great omnibus novel's first third, titled Penrod — after a fine buildup in which we learn how being systematically called a "little gentleman" can be no-end provoking — culminates in the Great Tar Fight. Here we get laughter that will stick to your ribs, surely one of the funniest passages I have ever read.

A lot of Penrod's adventures are in street, backyard, alley, and stable. Some are in, or against, institutional or organized environments such as school; dancing-class; a formal children's party with dancing. There is a fine account of sword-fighting with simple wooden swords, "severe outbreaks of cavalry" in the Schofield neighborhood. My own childhood enjoyed very similar sword-fighting, and this rings resoundingly true.

A hilarious highlight of Penrod and Sam is Penrod's school assignment to write "a model letter to a friend". The assignment does not fall on receptive ground:

If it were possible to place a romantic young Broadway actor and athlete under hushing supervision for six hours a day, compelling him to bend his unremitting attention upon the city directory of Sheboygan, Wisconsin, he could scarce be expected to respond genially to frequent statements that the compulsion was all for his own good. On the contrary, it might be reasonable to conceive his response as taking the form of action, which is precisely the form that Penrod's smouldering impulse yearned to take.

To Penrod school was merely a state of confinement, envenomed by mathematics. ...

With his own model letter unwritten, Penrod's last-minute attempt to swap in a letter by his older sister Margaret to her boyfriend — he hasn't time to read it first — meets with merited disaster. The fallout from this lasts well after school.

(A dystopian aside: Some imaginary later Era of Scientifically Righteous Correction of Children might label much characteristic behavior of Penrod and Sam as criminality, juvenile delinquency. Penrod's dislike of being schooled would be diagnosed as Attention Deficit Disorder, certainly with Hyperactivity (ADHD); experts could endeavor to squelch distraction and misplaced energies by treating millions of children with spirit-numbing drugs. But this imaginary era is surely too outrageous, such attitudes toward children could develop only in some science-fiction dystopia which is smotheringly destructive of creativity and exploration and all types of youthful exuberance.)

The boyish adventures keep coming. The feral cat named Gypsy who is captured for the boys' Jungle Show. The giant homemade snake which animates panic in surprising directions. The formal dance party whose distressing but hysterical chaos could hardly be strengthened by a mischievous tornado.

And there is a strong thread of young romance twisting in and out of the weave, of Penrod and the little girl Marjorie Jones. Penrod and Marjorie are shown in one of Gordon Grant's many fine black-and-white drawings, above.

The interracial aspects of neighborhood play may surprise later-generation readers brought up on politically-correct hostility, and derail those censorious librarians who fail to understand Huckleberry Finn. The racial division in Penrod's time and place appears in economics and education, but not geography or daily contact or play. Across the alley from Penrod's house lives a coloured family with two boys who become playmates, Herman and his younger brother Verman. These boys are well characterized, have different qualities than the white kids, but Tarkington makes it clear that they are social equals in backyard play, that is within the portion of society arranged by the children themselves. What's more, you would be very glad to have them on your side.

The interracial aspects of neighborhood play may surprise later-generation readers brought up on politically-correct hostility, and derail those censorious librarians who fail to understand Huckleberry Finn. The racial division in Penrod's time and place appears in economics and education, but not geography or daily contact or play. Across the alley from Penrod's house lives a coloured family with two boys who become playmates, Herman and his younger brother Verman. These boys are well characterized, have different qualities than the white kids, but Tarkington makes it clear that they are social equals in backyard play, that is within the portion of society arranged by the children themselves. What's more, you would be very glad to have them on your side.

In the sword-fighting wars mentioned above, little tongue-tied Verman, normally happy-go-lucky, is the true exemplar of chivalry:

Strangely enough, the undoubted champion proved to be the youngest and darkest of all the combatants. Verman was valiant beyond all others, and, in spite of every handicap, he became at once the chief support of his own party and the despair of the opposition.

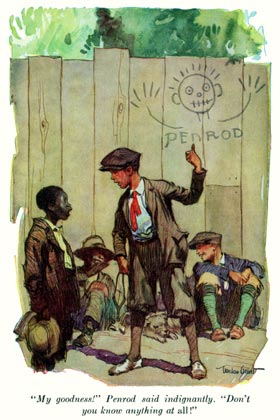

In Gordon Grant's color painting shown here, four of the boys are shown: Verman and Penrod standing, and Herman and Sam sitting against the fence.

Penrod Jashber, the final third of Penrod: His Complete Story, is less hilarious but more flowing as a single story, in fact a detective story wherein Penrod promotes himself to Detective and recruits his pals into his agency. This portion also impinges on the adult world with slightly closer to equal terms; and closes the book with Penrod's twelfth birthday.

Penrod: His Complete Story is a very American novel. It has aspects in common with great novels as different as Mark Twain's Huckleberry Finn and Ross Lockridge's Raintree County, and Carl Barks' superb comic-book tales of Donald Duck and neighborly Duckburg. Enterprise, audacity, fairness, and (eventually) good-feeling. Young Penrod Schofield lives in an era and state of mind where if things inevitably do not go quite right, nevertheless they go well. The justified, and understood, American optimism.

I am so lucky to have discovered Penrod when I was about his age myself. But it is not entirely luck, as Penrod and Sam was one title from several children's book-clubs which my Mother subscribed to for me. The adventures of Penrod and his friends brought me to laughter then and now, both in cheerful times and in times when jests were few. Booth Tarkington (1869-1946) won two Pulitzer Prizes for other novels, but I believe it is this one which places him among the Immortals.

There is a memorable episode when Penrod has been practicing the bullfrog's croak, and through maternal concern is treated with a tonic for nervous trouble. He suffers this until he hits on the idea of counterfeiting the tonic with natural materials at hand in the back yard, and thereafter feels much better. You can hardly do better for your mood than to treat yourself with regular laughter from Penrod: His Complete Story.

© 2005 Robert Wilfred Franson

Penrod: His Complete Story

interior illustrations, above left:

by Gordon Grant

WordPoints at Troynovant

reading & writing, editing & publishing

Juvenile at Troynovant

for a younger audience

| Troynovant, or Renewing Troy: | New | Contents | |||

| recurrent inspiration | Recent Updates | |||

|

www.Troynovant.com |

||||

|

Reviews |

||||

| Personae | Strata | Topography |

|

|||