The Day-Nite Garage

Eugene, Oregon

1939-1941

Leaving the big garage doors open

The Day-Nite Garage was well situated on Olive Street in the downtown business section of Eugene, Oregon from the 1920s to the early 1940s. We never closed our doors and there usually was something interesting going on there. We had a tow truck and an ambulance, and when an emergency call came in, whoever was available would take out the vehicles, leaving the big garage doors open, lights on, and sometimes nobody there. There were seven of us who were more or less regular employees, plus the owner, Jim Brown. Most of us had no specified hours of duty, but came and went pretty much on our own. The only regular shift was the all-night tour of the night mechanic, who handled repair jobs that had to be done right away, and also did major overhauls when he had the time.

We were told we were the only real full-service 24-hour garage on Highway 99 between Portland and the California state line. Could have been; I never had a chance to check on that. At that time Highway 99 went through downtown Eugene, close to our garage. We sold Veltex gasoline from our one pump located at the curb. My salary was $12 a week, plus a nickel on each gallon of gasoline. I kept the house vehicles full of gasoline and oil, and tried to sell gasoline to the storage customers. I also handled minor repairs such as fan belt replacements, tire changes, windshield wipers, etc., and kept the office and shop as clean as I could.

While I worked there I found the time to paint a map of Highway 99 on a ten-foot space of the front wall; I included the names of the major cities from the California state line to the Columbia River.

Because of our nocturnal life we saw the underside of life in Eugene. We made emergency repairs on police trucks and taxicabs, and our tow truck was kept busy attending to wrecks and disabled cars. When an emergency ambulance call came in, one of us would grab a white coat and cap, and take off in the 1939 Plymouth ambulance with the red light and siren going. It was fun now and then driving the wrong way down a one-way street, fully authorized to do so, with my thumb on the siren and watching oncoming cars peel away to either side.

One night my boss had to take care of a baby born in the ambulance, without dire consequences, and although I missed that experience I twice carried in people who died before we got to them, and several who died at the hospital. Once I carried a dead logger forty miles down a mountain road. He had been rolled on by a huge log, and the doctor I took with me on the call declared him dead and asked me to take the man to the morgue. I stopped on the way back to Eugene to get coffee and doughnuts, and the waitress, seeing the ambulance outside, asked me rather wide-eyed:

"Do you have a hurt man in there?"

I couldn't resist answering, casually,

"No, he's dead."

I could handle that, but the time I took in a nine year old boy who was burned in a house fire, it got to me when I learned the next morning that he had died at the hospital. My boss made me take two days off.

Driving an ambulance on an emergency call pumps up the adrenaline and you know that although you are entitled to the right of way, those red lights and the siren will not always clear the way for you. But there is no time to think about that; the driver's mind is concentrating on how to get there, which streets to take, where to turn, where to stop, how to handle the injured person, and how to get to the hospital. Most of our ambulance calls were non-emergency situations, carrying people to and from the two local hospitals.

Our ambulance was a long-wheelbase 1939 Plymouth, painted white. It had been modified to take a cot through the right side doors. The floor was flat and there were hooks for lashing the cot in place. The side door loading was convenient and left the big back seat available for carrying ambulatory passengers.

Our tow truck was an International with cables front and rear. One night I had the front cable pulling on a big truck that was stuck in soft mud and I had my rear cable wrapped around a big tree. When I turned on the winch I felt the tow truck start to rise off the ground. That scared me, so I quickly shut off the winch, looked for a phone, and got the boss out of bed. He brought our old standby tow truck, also an International, and together we extracted the stuck truck from the ditch. On some big jobs we had to block off a road while we worked, and I don't remember having any trouble about that. Of course we did not have any freeways then.

Our tow truck was an International with cables front and rear. One night I had the front cable pulling on a big truck that was stuck in soft mud and I had my rear cable wrapped around a big tree. When I turned on the winch I felt the tow truck start to rise off the ground. That scared me, so I quickly shut off the winch, looked for a phone, and got the boss out of bed. He brought our old standby tow truck, also an International, and together we extracted the stuck truck from the ditch. On some big jobs we had to block off a road while we worked, and I don't remember having any trouble about that. Of course we did not have any freeways then.

Most of our tow truck errands were dull, grinding, routine jobs, not as exciting and stimulating as the big wrecks. Once I took two gallons of gasoline to a man out of gas. He would not pay the fifty-cent service charge I asked him for, but he paid for the gas. I was not able to insist, so I poured the gas in his tank, wishing it was nitroglycerin. Times were tough then, and people fought for every nickel. Another example of the hundreds of frustrating and trivial situations will suffice here. Late one night a man drove in and said he was out of gas and out of money, but he would leave his spare wheel and tire as security for a tank of gas. I smelled fraud in that deal, but I let him have the gas. Three days late the same car came in, with a different driver. He said his son took the car without his permission and I shouldn't have let him have the gas. That was one of those no-win situations that all public service enterprises see every day.

The owner and his wife lived in a small apartment on the second floor of the Day-Nite Garage and they could see the other side of Olive Street from their front windows, but they could only guess what was happening in the garage below. It must have been a noisy place to live, with people and trucks coming and going all night. The second floor was used for car storage, and the floor boards creaked. The wooden ramp to the second floor also creaked and was sometimes slippery from oil drippings.

We did a good business in storage and parking. We had some steady customers who left their cars and trucks with us every night, and we did some business with people who wanted to have dinner or see a show downtown and didn't want to leave their cars on the streets. Some of our storage was long-term, and I remember one woman who kept her house trailer in our place for three months, living in it while she waited for a job she had been promised. We had several cars that hadn't been moved in months, and we even had an airplane on the second floor. The airplane owner worked on it from time to time, but never got it assembled.

The boss was easy-going and enjoyed talking with all kinds of people. Besides the people who belonged there, we often had a gathering of hangers-on who had nothing better to do and liked the warm and cozy garage office. Sometimes five or six would stand in the little office, and the talk was about the same from day to day, or night to night. Loafers also gathered in the back of the building, where the welding and heavy work was done. We had two areas where there was no loafing. The battery charging rack was too smelly, and the second floor was up the steep ramp and not worth the climb.

The local Buick dealer did not have enough storage space for his new car inventory, so he stored some new cars with us. We parked them on the second floor. Whenever the dealer wanted one of the Buicks for demonstration or delivery I had to run up to the second floor to get the car, drive it down the wooden ramp, and park it by the front door so the salesman could drive it away. The sight of all that power and glory was almost overwhelming, and I did a lot of daydreaming about how nice it would be to drive a new 1940 Buick convertible down a sunlit highway with a girl beside me. But I survived and so did the cars. I was lucky and didn't scratch one car.

I still like to hang around garages if I can find some excuses, but few are as fascinating as the Day-Nite Garage. I worked there from 1939 to 1941, when the high wages at Boeing attracted me, and after a few months at Boeing I enlisted in the Army Air Corps (later called the Air Force). When I came back to Eugene after World War II the old garage building had been taken over by a Kaiser-Frazer automobile dealership. The former inhabitants of the Day-Nite Garage had scattered and I could find only a few of them.

© 1999 Wilfred R. Franson

FOR SALE

ENTIRE OUTFIT DAY-NITE GARAGE

AND EUGENE AMBULANCE CO.

LOCK, STOCK AND BARREL

The war is over, I am tired and want a rest,

you take my place.

Good setup with plenty of business in a healthy condition.

J. H. BROWN

Eugene

Eugene Register-Guard, 21 October 1945

The Day-Nite Garage

with its ambulance & tow truck

Eugene, Oregon 1939

[I drove these vehicles daily. — WRF]

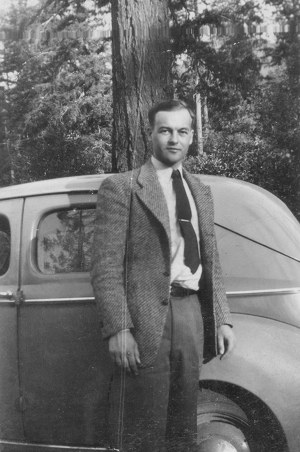

Wilfred R. Franson

McKenzie Pass

east of Eugene, Oregon 1940

Luck versus Auto Accidents

With Some Scrapes and Escapes

Day-Nite Garage's tow truck

rainy day

Eugene, Oregon 1940

More by Wilfred R. Franson

Transport at Troynovant

ships, trains, autos,

aircraft, spacecraft

The Eugene Post Office

Eugene, Oregon 1949-1956

| Troynovant, or Renewing Troy: | New | Contents | |||

| recurrent inspiration | Recent Updates | |||

|

www.Troynovant.com |

||||

|

Essays:

A-B

C-F

G-L

M-R

S-Z

|

||||

| Personae | Strata | Topography | |

|

|||