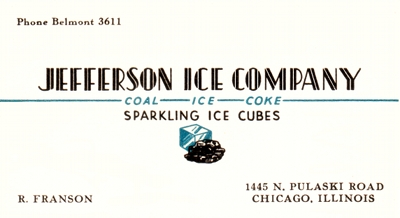

The Jefferson Ice Company

Chicago, Illinois

1927-1929 (part-time & summers),

1933-1936

Natural and artificial ice

My father Robert Franson worked for the Jefferson Ice Company in Chicago for thirty years, 1911 to 1941. Before "artificial ice" (made at the ice plant by a huge freezing process) he worked for other employers, cutting and transporting "natural ice", which was cut from frozen lakes almost exactly as Henry Thoreau had described in his stories about Walden Pond about a century before.

One of my father's jobs in the early days was driving trucks loaded with "natural ice" from the lakes to the Chicago ice houses. He told me he felt ridiculous driving a big, slow truck loaded with ice in the Chicago winter with snow and ice on the ground.

One of my father's jobs in the early days was driving trucks loaded with "natural ice" from the lakes to the Chicago ice houses. He told me he felt ridiculous driving a big, slow truck loaded with ice in the Chicago winter with snow and ice on the ground.

[That's not my father in this photo, but the truck is one of a series of strong ice haulers.]

When the ice companies switched from the easily-contaminated "natural ice" to the sanitary "artificial ice" made from clean and filtered city water, some consumers objected to the ammonia smell at the ice plant, and were convinced that the "artificial ice" contained ammonia. Actually, the ice was cleaner than the city water because it was put through additional filters, and the 20 degrees Fahrenheit freezing process further purified the water.

The Jefferson Ice Company was named for Jefferson Township, a largely residential area with a lot of open space, on the northwest side of Chicago. It was incorporated into the city of Chicago in 1889.

The Jefferson Ice Company had several ice manufacturing plants, and my father worked his way up to superintendent, with as many as 400 men making and hauling ice to the ice plants, where the retail delivery horse wagons and trucks (mostly individually owned) loaded their rickety vehicles and cruised up and down the streets, selling the ice in 25- to 100-pound chunks.

The Jefferson Ice Company had several ice manufacturing plants, and my father worked his way up to superintendent, with as many as 400 men making and hauling ice to the ice plants, where the retail delivery horse wagons and trucks (mostly individually owned) loaded their rickety vehicles and cruised up and down the streets, selling the ice in 25- to 100-pound chunks.

Every retail ice wagon and truck carried a scale hanging on the back of the vehicle. That was important in the early days, before the ice plants had "scoring machines" that cut grooves in the cakes to mark off 50-pound chunks in the "400-pound" ice cakes; the Chicago cakes actually weighed 420 pounds; a little (5%) was added because inevitably there was some shrinkage by melting on a hot day. Some customers asked to have their ice weighed.

Wholesale deliveries to butchers, movie theaters (to cool the air inside by blowing the air over several tons of ice), soda fountains, and other retailers of perishable items were serviced by the Jefferson Ice Company with their own trucks.

During my high school years I spent some of my Saturdays handling the retail customers who brought their vehicles (cars, children's wagons, and wheelbarrows) and hauled it home themselves. I had to learn how to lower a 75-pound chunk into a child's wagon without dropping it. The platform was about four feet above street level (to match the height of the truck bodies), and I was a skinny kid of only 120 pounds, so I dropped a few, fortunately without injury to anyone. Some people brought their cars, and carried the ice on their front bumpers, on the front floor, on an outside trunk rack in the back, and a few in the rumble seat or trunk.

The ice business in Chicago was totally unionized, but in 1929 I was considered a "clerk" because I counted the money and made a daily report on total sales, so I was not allowed to join the union.

In 1933, after working elsewhere for three years, I went back to the ice company and helped to load the big trucks that carried loads of ice between ice plants. By that time I had put on some beef by surviving some extremely physical jobs. I also clerked and wrote the daily reports.

In 1933, after working elsewhere for three years, I went back to the ice company and helped to load the big trucks that carried loads of ice between ice plants. By that time I had put on some beef by surviving some extremely physical jobs. I also clerked and wrote the daily reports.

The 420-pound cakes of ice were placed on a moving conveyor inside the warehouse and would come out through a swinging door onto the loading platform, where two men with ice tongs and working together like parts of a machine would load the trucks.

One man (sometimes I) would straddle each ice cake as it slid through the door, grab the cake with the ice tongs and lift it to a vertical position. That was a straight lift of 210 pounds (one end of the cake), and the other man (in the truck) would grab the ice and slide it into the truck, making a neat load. The cakes were stood on end because that way they could get more ice in each load. It was hard but I had a chance once to load a truck with ice cakes lying on their sides; it was much harder to load and unload, and lifting the 420-pound cakes three high was awkward and very hard for two men.

In the winter of 1932-33 I was the night watchman in the Springfield Avenue ice plant, and an ice plant in the middle of the night in the cold Chicago winter was a lonesome place. The ice-making machinery was started up only when there was a "warm spell" (outside temperature above 20 degrees Fahrenheit). We had to keep the warehouse at 20 degrees.

I learned how to start and stop the ammonia compressor when necessary. I made a complete tour of the engine room, ice-making tank room, basement, loading platform, and storage room once every hour.

I did a lot of reading in the office between inspection tours. There was a railroad in back of the plant, and I could hear (and feel) the heavy freight trains. The warehouse was lined with cork, and sometimes I amused myself by throwing ice picks at a target on the wall. I got to be pretty good at it.

I left the Jefferson Ice Company when Western Electric called me back to work in 1936.

My father, who was promoted to superintendent in 1920, was issued a Model T Ford coupe, and in addition to his duties as a supervisor, he cruised up and down the main streets of the Northwest side looking for new enterprises, such as butcher shops, to sell them on the superior service offered by the Jefferson Ice Company. He was very good at that, and he did provide good service.

My father, who was promoted to superintendent in 1920, was issued a Model T Ford coupe, and in addition to his duties as a supervisor, he cruised up and down the main streets of the Northwest side looking for new enterprises, such as butcher shops, to sell them on the superior service offered by the Jefferson Ice Company. He was very good at that, and he did provide good service.

For example, he arranged ice delivery to kosher shops on the sabbath; he would obtain the keys, open up for the ice delivery, and lock up again, always respecting the traditions.

© 1999 Wilfred R. Franson

Jefferson Ice Company truck

circa 1921

Cold at Troynovant

cold weather and winter environments,

survival, exploration in high altitudes,

polar regions, other planets

Jefferson Ice Company

photo by Wilfred R. Franson, 30 July 1945

More by Wilfred R. Franson

| Troynovant, or Renewing Troy: | New | Contents | |||

| recurrent inspiration | Recent Updates | |||

|

www.Troynovant.com |

||||

|

Essays:

A-B

C-F

G-L

M-R

S-Z

|

||||

| Personae | Strata | Topography | |

|

|||