The End of the Line

by James H. Schmitz

collected in —

"The End of the Line" is one of James Schmitz's earlier stories, originally published in 1951. It was anthologized a few years later in Space Pioneers, edited by Andre Norton, where I read it when I was in elementary school. Something like twenty years later, I found a used copy of Space Pioneers and bought it in order to reread "The End of the Line", which had stuck in my memory as an interesting story. Rereading it as an adult, I still found it enjoyable — and I realized that a lot of it had passed quietly over my head when I first read it.

Schmitz's novelet is based on a trope that is now common in comic books, though it wasn't so in 1951: the group of adolescents or young adults with unusual abilities, banded together as a self-contained community. Schmitz's characters are eight adolescents nearing adulthood and one adult leader, Grevan, all with superior bodies and minds, psionic abilities and resistance to mental domination, and a superhumanly adaptable metabolism. All of them are creations of an organization called Central Government, products of a long-term controlled breeding program. The story finds them landing on a remote, unknown Earthlike world, where they hope to escape from Central Government's control.

Central Government is only sketched briefly, but it's a classic science fictional totalitarian society, with powerful bureaucrats whose plans stretch centuries into the future, mind control machines, and a helplessly dependent populace incapable of surviving on their own. One of the most striking details, brought out several times in the story in different ways, is that the food in this future civilization comes entirely from tissue cultures grown in nutrient solutions, and contains no natural toxins or allergens, and as a result normal human beings have lost the ability to process natural foods, to such a degree that eating anything other than cultured food is a death sentence. In contrast, one of the key powers of Schmitz's protagonists is a superhuman ability to adapt to new biochemical challenges. Schmitz has taken the contrast between the specialist unable to survive outside the social machine he serves and the independent generalist from social and behavioral to the physiological level.

The primary conflict in "The End of the Line" grows out of this situation. The secondary conflicts involve different ways of dealing with the primary conflict and different reactions to it.

In showing these complications, Schmitz illuminates the younger characters, though not as much as Grevan. At some point in the narrative, each of the eight younger characters is in the spotlight, as a distinctive individual, however briefly sketched — which makes the point that part of what is valuable in them is precisely that individuality. In addition, Schmitz establishes who has paired off with who, and in doing so raises the problem that's the other engine for this story's plot: the fact that Grevan was not provided with a mate. The working out of the storyline ingeniously links these two issues together, on more than one level.

The tone of "The End of the Line" is light, and it can be read as straightforward action / adventure, or even comedy. But its themes are serious. It's a mark of Schmitz's skill as a writer that he manages to convey them without letting them weigh the story down. I've read a lot more of Schmitz since then, but this story remains my favorite of his, and for more than sentimental reasons.

© 2005 William H. Stoddard

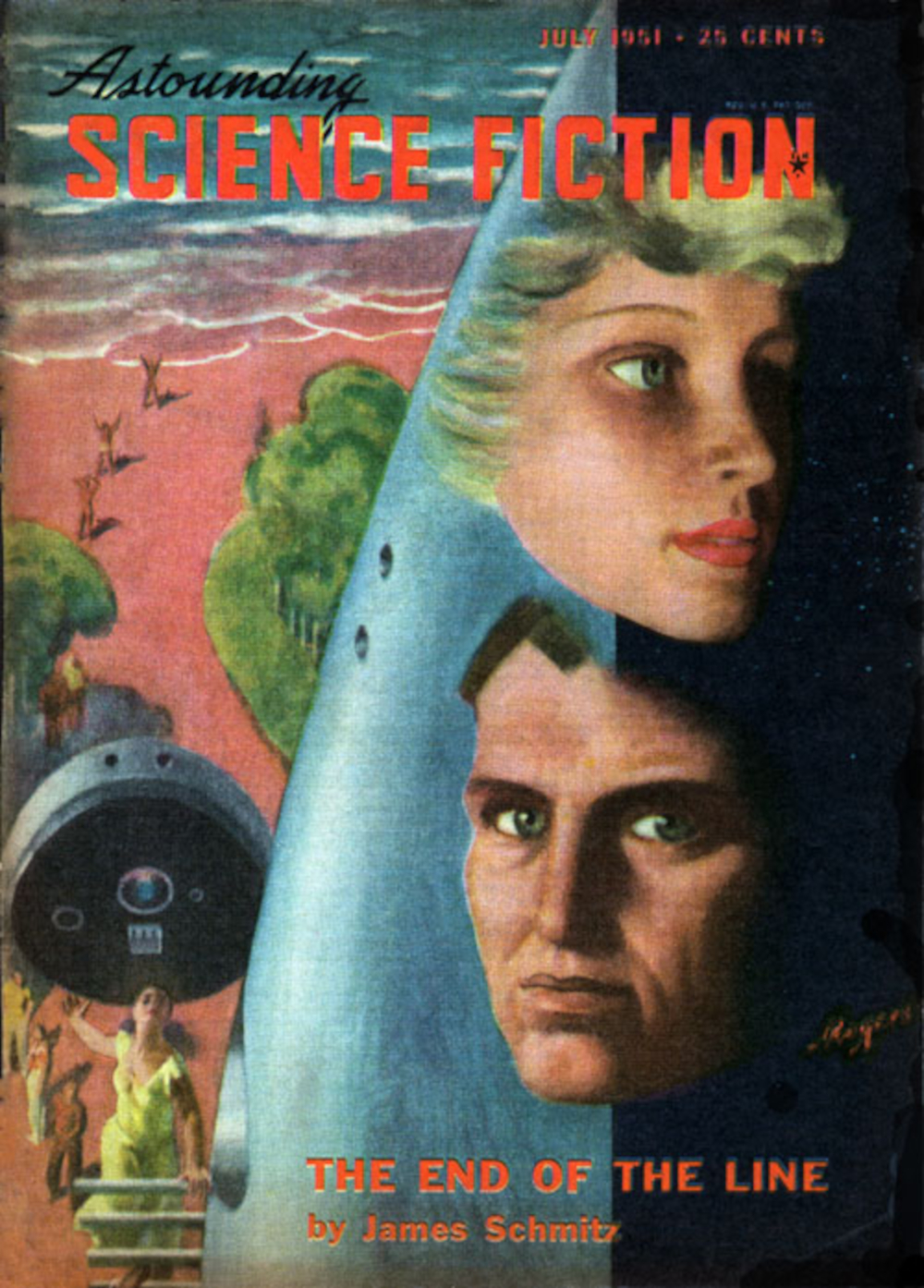

magazine cover, bottom:

Astounding July 1951

by Hubert Rogers

Mentality at Troynovant

the mind & mental operation

More by William H. Stoddard

Utopia at Troynovant

utopia in power, or dystopia

| Troynovant, or Renewing Troy: | New | Contents | |||

| recurrent inspiration | Recent Updates | |||

|

www.Troynovant.com |

||||

|

Reviews |

||||

| Personae | Strata | Topography |

|

|||