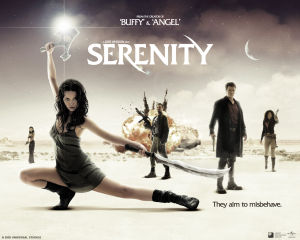

Serenity

Director: Joss Whedon

Writer: Joss Whedon

Music: David Newman

Cast:

- Nathan Fillion — Malcolm Reynolds, captain

- Morena Baccarin — Inara Serra, registered companion

- Adam Baldwin — Jayne Cobb, marksman

- Ron Glass — "Shepherd" Book, chaplain

- Summer Glau — River Tam

- Sean Maher — Simon Tam, doctor

- Jewel Staite — "Kaylee" Frye, engineer

- Gina Torres — Zoe Washburne, 1st officer

- Alan Tudyk — "Wash" Washburne, pilot

- Chiwetel Ejiofor — The Operative

- Rafael Feldman — Fanty

- Yan Feldman — Mingo

- Michael Hitchcock — Dr. Mathias

- David Krumholtz — Mr. Universe

- Sarah Paulson — Dr. Caron

- Nectar Rose — Lenore

- Tamara Taylor — Teacher

- Hunter Ansley Wryn — young River Tam

Universal: 2005

If you have not read our review of Firefly,

please read that first. The Serenity movie

is a sequel to the Firefly dvd series.

Warning: major plot spoilers in the following review,

intended for those who have seen Serenity.

Sustained artistic intent

After I first saw Serenity, I didn't feel ready to write about it immediately. It seemed to require a carefully thought out response, and I hadn't had time to develop one; all I had was emotional reactions and first impressions. Now, though, after a few weeks, those impressions are falling into a kind of order. So here are some comments on what kind of film Serenity is and what it's about.

In the first place, this is very definitely a film that grows out of sustained artistic intent. The German filmmaker Fritz Lang reputedly had a sign in his office that read, "Nothing in this picture is accidental." Joss Whedon's television work showed the same spirit; now in this film we have the pleasure of seeing a complete work where everything is chosen to fit a conscious design. There are no jarring notes or accidental elements. This is a rare pleasure in American film and television.

In the second place, the story of the film is not just an excuse for the action. There's real intellectual substance. It's a secondary pleasure, but a real one, that this substance is so congruent with libertarian political values.

Friedrich Hayek wrote about the distinction between two sorts of liberalism — the constructive liberalism of the French Revolution, in which the government sought to transform social institutions, culture, and perhaps humanity itself, an aspiration that gave rise to the social engineering projects of the 20th Century; and the classical liberalism of the American Revolution, in which the government sought to establish a legal framework within which people could independently pursue their own goals, an outlook that was largely forgotten in the 20th Century but has begun to be rediscovered in the 21st.

The Alliance of Serenity's setting is clearly in favor of social engineering in a big way; the heroes of Serenity stand in opposition to the remaking of humanity — and, as an implication, to the vision of the future that was central to Hugo Gernsback's original definition of "scientifiction" and to many works that followed from it.

There's a thesis held by some libertarian science fiction fans that support for libertarian values is a natural element of science fiction. But large parts of the genre's history not only fail to support this, but show active opposition to those values. H. G. Wells, who created the first wave of "big ideas" that are still current in science fiction (in contrast to Jules Verne, whose earlier big ideas are now too much a part of everyday reality to inspire speculative novels), was a lifelong advocate of socialism. Olaf Stapledon, another early fountainhead of ideas, envisioned the enlightened societies of superior beings as communistic and sometimes even as dictatorial. The Futurians, one of the first influential factions within science fiction fandom, were solidly leftist in outlook. In many ways, the better future that this kind of science fiction envisions is a socialist future, with key decisions made by scientific experts.

Now, in Serenity, the audience is presented with exactly that future. The inner worlds of the Alliance are shining, clean, high-tech utopias ... and their political leaders want to make everyone fit into their ideal future, at any price. They're willing to wage a war of conquest against worlds that don't join in with their plans; to send out secret agents not bound by law or morality; to mutilate the brain of a brilliant adolescent girl in the hope of making her a tool they can use. The cliche science-fictional future is shown as a heaven that is not worth entering.

Now, in Serenity, the audience is presented with exactly that future. The inner worlds of the Alliance are shining, clean, high-tech utopias ... and their political leaders want to make everyone fit into their ideal future, at any price. They're willing to wage a war of conquest against worlds that don't join in with their plans; to send out secret agents not bound by law or morality; to mutilate the brain of a brilliant adolescent girl in the hope of making her a tool they can use. The cliche science-fictional future is shown as a heaven that is not worth entering.

On the other side, we have a more rough-hewn future — the future of a minority in science fiction, whose best known representative is Robert Heinlein. The primary metaphor of this sort of science fiction is that outer space is a frontier: to be explored, colonized, and fought over, by tough, practical men (and women) with simple tools. This is a theme with special appeal for Americans (and also for Russians, who had their own frontier), and it made it into televised science fiction once before, in Star Trek, pitched to network executives as "Wagon Train in space" (though the word "trek" evokes the frontier societies of southern Africa, and in practice Star Trek was more "Horatio Hornblower in space", emphasizing the naval bureaucracy of Starfleet over the settlers on various planets — and in the later series the Federation came closer to the Gernsbackian technocratic vision).

Whedon has picked up that vision, and given it a rationale, more or less the same one Heinlein offered: Horses can make more horses, and that's a trick tractors have never learned. In his setting, the smaller colonies are a rather Heinleinian frontier society. They're not as rich as the core worlds, or as sophisticated, and they have their own biases and injustices, but they offer independent-minded people a chance to establish themselves — as Malcolm Reynolds and his crew have done. But this vision of the future conflicts with that of the advocates of a planned and controlled society, and the plot of Serenity grows out of that conflict.

The third thing worth noting about Serenity is its theme. This is not primarily political. It's stated explicitly in the opening scenes, when the Operative, discussing a holographic video recording of River Tam's escape, identifies the expression on her older brother's face as love, and says that love is dangerous.

It's restated in the final scene, when Malcolm Reynolds says to River that it's love that keeps a ship flying when it ought to break down. (Given the history of the film, this can easily be read as a comment about Whedon's own fictional project, sustained by the devotion of Firefly fans despite incredibly bad handling by the Fox network.)

relationships we care about

And in between, scene after scene evokes the same theme, between various pairs of characters:

- Simon and River, in the opening scene and throughout

- Kaylee and Simon, whose awkward courtship takes a long-delayed step forward

- Mr. Universe and his robot bride (a somewhat satiric parallel to Mal and his ship)

- Mal and Inara, whose attraction to each other makes both their lives difficult

- Mal and Book, a fine example of friendship rooted in character and unaffected by disagreement of beliefs

- Zoe and Wash, the film's established couple

- Mal and Zoe, as two old soldiers who have learned to trust each other completely

This recurring theme is what makes the film's characterization so good. The old cliché about science fiction is that it's about gadgets rather than people; but Whedon's future is inhabited by people, and nothing defines people so well as who or what they love. Serenity is full of characters and relationships. Even the ship Serenity is not merely a gadget, but a character, and its crew have a relationship with it as well. And every scene invites the viewer to care about the ship, the crew, and what kind of future they have ahead of them.

And ultimately, this does tie in with the political theme. The Operative is correct: love is dangerous. It's an expression of individuality — of personal choice — and the ideal technocratic future that he serves is one that limits personal choice. It wants, not hard, unbreakable stones, but soft, pliable masses, or even a homogenous fluid. This is a familiar conflict in our own 21st Century world; Whedon has expressed it in a fantastic milieu where it can be brought into sharper focus.

This is a film of ideas as well as a film of character, and both aspects create some depth behind the polished surface of action scenes and special effects.

© 2005 William H. Stoddard

R. W. Franson & D. H. Franson's

review of Serenity

ReFuture at Troynovant

history of science fiction

& progress of fantasy

More by William H. Stoddard

| Troynovant, or Renewing Troy: | New | Contents | |||

| recurrent inspiration | Recent Updates | |||

|

www.Troynovant.com |

||||

|

Feature Films: Queen Mab's ride |

||||

| Personae> | Strata | Topography |

|

|||