The Null-A series

by A. E. van Vogt

The World of Null-A, Astounding Science Fiction, Aug-Sept-Oct 1945

revised for book editions —

Simon & Schuster: New York, 1948

256 pages

The Players of Null-A, Astounding Science Fiction, Oct-Nov-Dec 1948

revised for book editions —

as The Pawns of Null-A

Ac:e: New York, 1956

254 pages

most later editions as The Players of Null-A

Warning: a few plot surprises are discussed below,

but we hope this will encourage prospective readers of the novels.

Plots and memories

As we begin —

Sane and determined ... but forgetfulHe [Gilbert Gosseyn] felt himself aloof from the materialism of Earth. In a completely unreligious sense, he longed for spiritual surcease.

A knock on the door ended the thought. He opened it and looked at the boy who stood there. The boy said, "I've been sent, sir, to tell you that all the rest of the guests on this floor are in the sitting room."

Gosseyn felt blank. "So what?" he asked.

"They're discussing the protection of the people on this floor, sir, during the games."

"Oh!" said Gosseyn.

He was shocked that he had forgotten. The earlier announcement coming over the hotel communicators about such protection had intrigued him. But it had been hard to believe that the world's greatest city would be entirely without police or court protection during the period of the games. [...]

"I'll be right there," smiled Gosseyn. "Tell them I'm a newcomer and forgot. And thank you."

Well, actually author A. E. van Vogt quickly forgets too. This scene, very near the beginning of The World of Null-A, shows some of the deep problems of the Null-A novels: flaws of structure in the first novel, and of practical philosophy in both novels. The anticipated lawlessness in the streets is recalled a few times by Gosseyn, but never develops. No matter, we're quickly on to bigger things.

He is in town to compete in examinations held by the Games Machine to periodically choose recruits into the professional upper crust of Earth, a mandarin class objectively chosen by the objective Games Machine. Unfortunately for Earth, the Games Machine has been corrupted.

The Games Machine recognizes that Gosseyn isn't who he thinks he is. The blankness referred to above is perhaps a sign of being a person inhabiting a body grown to young adulthood in a vat. His antecedent memories are faked, laid in for a purpose unknown to him. Finding out who put him into the world like this is Gosseyn's main purpose in The World of Null-A. In the succeeding novel The Players of Null-A, the game board extends spectacularly beyond Earth and Venus to the galaxy.

These novels rush us along, not merely at a mundane fast pace, but at a stellar teleport-pace. Despite confusions, they were and still remain riveting to read and thought-provoking: tremendous science fiction of the rare breed that thinks, reaches, and moves.

Gosseyn may be pronounced go-sane. How the human mind works is the major theme of the Null-A books. Van Vogt based these novels on General Semantics, a philosophy developed by Alfred Korzybski in Manhood of Humanity (1921) and Science and Sanity (1933; third edition 1948). "Null-A", properly inscribed as a letter "A" with a negating bar over the letter, stands for non-Aristotelian. Korzybski aimed to overthrow classical logic and other allegedly simplistic and outmoded legacies of Aristotle. In his works Korzybski developed what he regarded as a modern and scientific mode of thinking and thus of living.

By the time set for the Null-A stories in the 2500s, the Institute of General Semantics has been the government of Earth for five hundred years. Null-A trained people run Earth, and later through control of the colonization of an Old-Wet style Venus, settled that planet only with their own null-A people. Venus in the 2500s is a null-A utopia.

Eldred Crang, a null-A detective on Venus, is one of the key players in the Null-A series. (Venus used to be hidden under its perpetual clouds; postulate a terraformed Venus if you like, to explain its pleasant air and three-thousand-foot tall trees.) In a bookcase in Crang's tree-house on null-A Venus are some interesting futuristic titles, including Detectives in a World without Criminals. Too bad Gosseyn doesn't pick up that volume to look at, and share with us. Venus has 240 million inhabitants, all null-A trained. This anarchistic / communist society has detectives — but no criminals?

This paradox is reminiscent of authoritarian states who boast of crime-free streets, while the secret police execute thousands or even hundreds of thousands, and millions more languish and die in concentration camps. We don't get to see much of the null-A utopia on Venus.

In The World of Null-A, van Vogt's Gordian-knotted plot is complex for a not-very-long novel. Going into The Players of Null-A this knottiness is redoubled, faster than the narrative can untangle the plot and explain it.

In his fascinating 1947 essay, "Complication in the Science Fiction Story", van Vogt describes how he composed in 800-word scenes, and in each scene introduced a new sub-plot, a new significant character, or both. The Null-A stories do move fast, but you won't see much of the surroundings along the way. A narrower focus could have allowed details to accumulate, for instance about non-Aristotelianism in full bloom on Venus; then we'd have some intriguing pictures. But after a few scenes we switch planets; and then again; and then to a ship in space; and so on. The earlier Weapon Shop series, although complex, at least takes place almost entirely on Earth.

I want to emphasize, however, that the second Null-A novel is vastly better thought-out and integrated than the first. The deft interweaving of The Players of Null-A entirely outshines the first novel: characters and scenes are much more various, interesting, and fleshed-out, and the plot's surprises and re-doublings are a wonder to behold — even after repeated re-readings.

When our protagonist Gosseyn is killed by foes of null-A, a second Gosseyn body (Gosseyn II) is automatically activated with the up-to-the-minute memories and subjective self of Gosseyn I. Thus he has a kind of serial immortality, a valuable trait very disconcerting to his enemies.

Why enemies? Everyone around Gosseyn senses that he is a man of enormous potential, likely through unknown means to upset their power-politics game board.

The Gosseyn bodies each possess a secondary brain jammed into their skulls. Using this, Gosseyn develops an interesting way to teleport himself. It involves memorizing a stretch of ground or floor to "twenty-decimal similarity". Thereafter, during the single day that each location remains sharp in his memory, he can teleport himself to his memorized locations. There are conditions under which this doesn't work, but this similarization allows him to survive some sticky situations.

The Gosseyn body death-and-replacement is used only once in the novels. This concept easily might have been developed further; but in The Players of Null-A we get some exotic variations.

In The Players of Null-A Gosseyn is surprised to find himself in another person's body — not one of the Gosseyn-bodies, but that of the deposed Prince Ashargin — in a far star-system. Shortly he is taken to meet an interstellar emperor, Enro the Red:

The bathroom was built of mirrors — literally. Walls, ceiling, floor, fixtures — all mirrors, so perfectly made that wherever he looked he saw images of himself getting smaller and smaller but always sharp and clear. A bathtub projected out from one wall. [...] Water poured into it from three great spouts, and swirled noisily around a huge, naked, red-haired man who was being bathed by four young women. He saw Gosseyn, and waved the women out of the way.

They were alert, those young women. One of them turned off the water. The others stepped aside.

Yes, bathers of an emperor should be alert for commands. In a short interval, Gosseyn uses his null-A training a dozen times to keep the pitiable prince's body from passing out from the shock of meeting Enro. Even for a serf meeting a Tsar, this is overdrawn. Getting out of the bathtub, Enro says:

"I like women to bathe me. There is a gentleness about them that soothes my spirit."

Gosseyn said nothing. Enro's remark was intended to be humorous, but like so many people who did not understand themselves he merely gave himself away. The whole bathing scene here was alive with implications of a man whose development to adulthood was not complete. Babies, too, loved the feel of a woman's soft hands. But most babies didn't grow up to gain control of the largest empire in time and space.

Even reading this as a teenager I thought that not Enro's remark, but Gosseyn's Freudian analysis, was quite funny. It's a poor science of the mind in which men shouldn't enjoy womanly contact (and vice-versa, if not by imperial command). Perhaps Gosseyn's scant weeks or months of real memories, not including living through babyhood and childhood and youth, has left him emotionally flat. He is distant or puzzled concerning the people he meets, and avoids erotic involvement even when invited.

To be fair, van Vogt provides here few characters notably worth liking. Only Eldred Crang, the null-A detective, merits Gosseyn's respect. The Follower, a weirdly not-quite-present principal character in The Players of Null-A, is one of van Vogt's most striking creations but has his own problems.

Especially in the first novel, Gosseyn is a poor exemplar of clear, evaluative thinking of the purported Science and Sanity mode:

He was conscious of a vague dissatisfaction, an inexplicable sense of frustration.

When Gosseyn II is taken to view his shot-dead previous body, Gosseyn I:

They went down several flights of stairs and along a narrow corridor to a locked door. Crang unlocked it and pushed it open. Through it, Gosseyn had a glimpse of a marble floor and of machines.

"You're to go in alone and look at the body."

"Body?" said Gosseyn curiously. Then he got it. Body!

This sort of reaction is what I term the van Vogtian curse of surprise, and Gosseyn has it in good measure. Despite his null-A mastery and approved sanity, Gosseyn, or go-sane, has still a long way to go in the realm of common comprehension. Damon Knight at the dawn of his critical career (in a 1945 essay collected in In Search of Wonder) was merciless about such failings, but many of them survived van Vogt's revisions.

And by the showing here of General Semantics and null-A, in ruling Earth and virtually defining Gosseyn, have not merely a long way to go but on the wrong road altogether.

Venus and the null-A detective Eldred Crang promise better, but we do not see much of Venus except for the tree-houses; and Crang's motives are buried, his actions secretive — a deep player. If Gosseyn did not frequently reassure us of Crang's null-A commitment and expertise it would be hard to remember whose side he is on. What happens when a detective dies? (Of old age, presumably.) Among the null-A colonists on Venus, one succeeds to a job after discussion "as a result of a vote among the applicants". This is an odd resurgence of the medieval guild system rather than a free economy.

Is General Semantics a good choice as a ruling philosophy for a positive utopia, fictional or otherwise? A movement that claims to define what is sanity and what isn't, takes or wishes to take upon itself a lot of responsibility. Thomas Szasz, the great libertarian opponent of coercive psychiatry, says of the semanticists that:

Merging psychiatry and the StateIgnoring that the idea of insanity receives its nourishment from roots deeply buried in psychiatry and the law, they simply appropriated the concept and proceeded to give it their own meaning: Insanity was the improper use of language. [...]

In short, the semanticists did nothing to challenge the theoretical premises and social practices of psychiatry; instead, they hitched their wagon to its economic star and used the idea of insanity to aggrandize themselves and legitimate their self-styled science.

Thomas Szasz

Insanity: The Idea and Its Consequences

The Games Machine as selector of the ruling class of Earth nicely fits Szasz's condemnation of "the uncritical acceptance of the psychiatrist's judgment of who is sane and who is insane". In Szasz's Summary Statement and Manifesto, right after the prime principle of the metaphorical nature of the myth of mental illness comes an important corollary, separation of psychiatry and the State.

General Semantics as portrayed in the Null-A novels proudly reverses this principle, and has been a utopia in power over Earth for half a thousand years. This psychiatric technocracy rules the State. So what have the null-A experts done for Earth in these five hundred years? — Aside, that is, from exclusively colonizing Venus, rather as the Soviet Communist nomenklatura rewarded themselves with countryside dachas and holidays at Black Sea resorts.

These stories surely move fast and excitingly, but what is the culture actually doing? It is perhaps not sufficiently appreciated by readers of the Null-A novels that if the heroes and ruling class are null-A certified sane, the great majority of the inhabitants of Earth are relegated to the emotional darkness, sub-certified non-sane.

Not only does this remain so after half a millennium of null-A rule, but when The World of Null-A opens, the null-A experts have lost control of Earth's government to a cabal of native crooks and interstellar agents. Regardless of Gosseyn's entrancing adventures, this is not a good prospect for the long future of Man.

© 2002 Robert Wilfred Franson

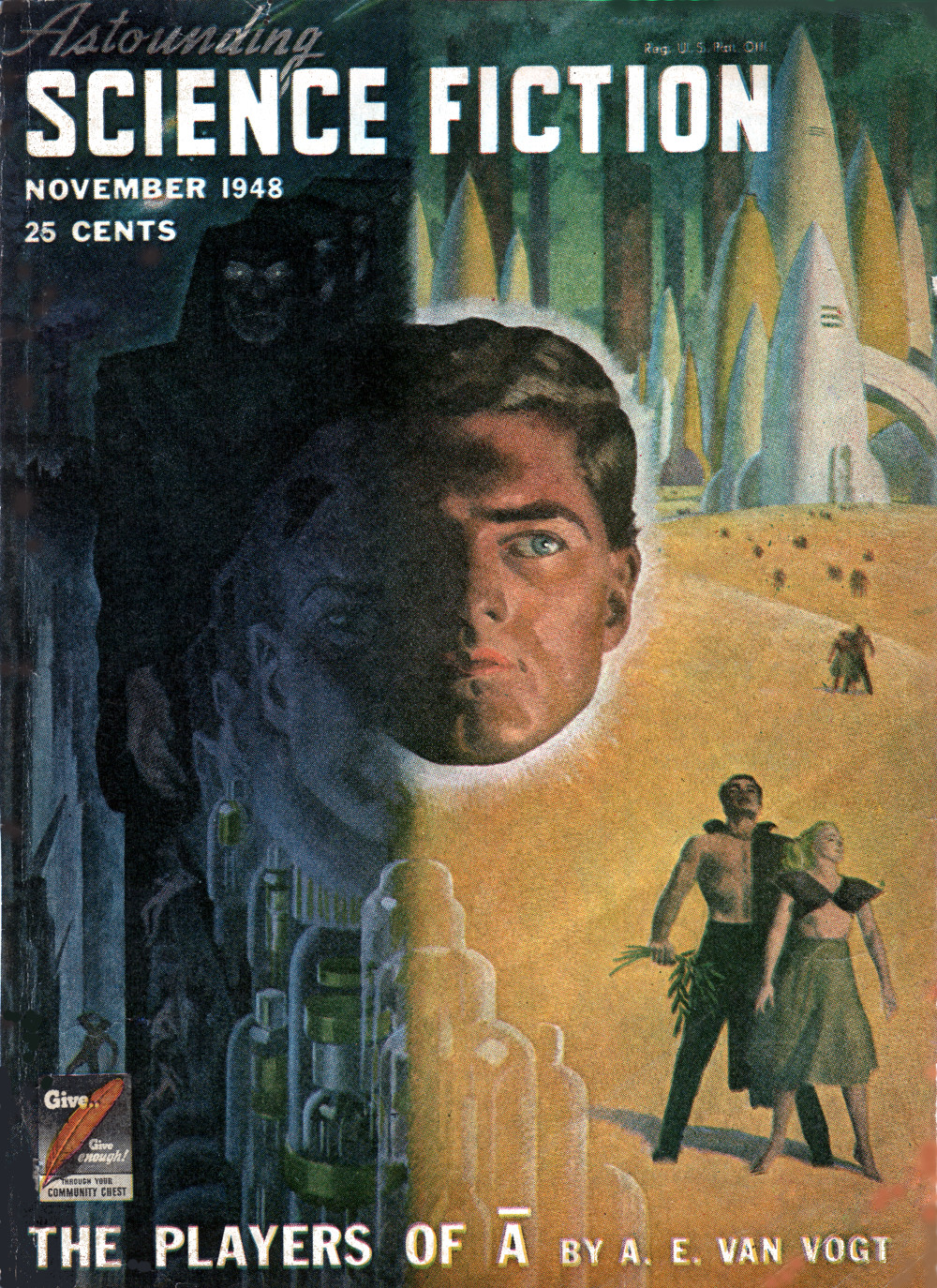

magazine cover, bottom:

Astounding, November 1948

by Hubert Rogers

Detection at Troynovant

solving mysteries; detective agencies

Livelong at Troynovant

longevity & immortality

Mentality at Troynovant

the mind and mental operation

Philosophy at Troynovant

nature of existence; history of ideas

Remembrance at Troynovant

memory, remembering, & fame

Transport at Troynovant

ships, trains, autos, aircraft, spacecraft

Utopia at Troynovant

utopia in power, or dystopia

| Troynovant, or Renewing Troy: | New | Contents | |||

| recurrent inspiration | Recent Updates | |||

|

www.Troynovant.com |

||||

|

Reviews |

||||

| Personae | Strata | Topography |

|

|||